The ITAK/TNA keeps denouncing successive Sinhala leaderships for not ‘building upon’ and/or “going beyond” the 13th amendment, but it was precisely in the Tamil interest—not so much that of the Sinhalese—to make the 13th amendment work so as to “build upon it” and “go beyond it”. That was primarily the responsibility of the Tamil leadership. Why didn’t it do so, as the Sinn Fein so brilliantly did with the Good Friday Agreement and the ensuing devolved structures?

“Provincial Councils Abolished!” screamed the headline of a mainstream, long-established, Sinhala-language Sunday newspaper (30 Jan 2022) sympathetic to the Sinhala nationalist cause. The byline of the story is that of a relatively young, intelligent journalist of ultranationalist orientation with excellent sources in the camp of the hawks that grew into President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s inner-circle.

The reporter claims that the draft of the new Constitution which is to be presented to the President next month and then to the Cabinet and Parliament, excludes the system of Provincial Councils and pretty much restores the 1972 Constitution, including the post of an empowered Prime Minister as the leader of the country, thereby abolishing the executive presidency.

Trapped Opposition?

The report concludes that the Government expects the new Constitution to replace the current one, within this year.

In the absence of any contradiction, one may deduce that there is a fire behind the smoke. It is likely that the lead story is based on the submissions of one or more members of the drafting committee.

If the sentence about the replacement of the elected executive Presidency by a Prime Minister is true, then the Opposition is caught in a trap of its own making. A referendum would be the earliest and best chance to break the back of the regime and expedite its end – which is how Pinochet went—but how is the Opposition to call for a NO vote when – with the possible, partial exceptions of the SJB and SLFP—much of the oppositional opinion space is ideologically and intellectually committed to the abolition of the executive presidency?

If the principle is opposition to the centralisation of power, then it is surely at least as bad in the hands of the PM as the President; in fact, it is worse because the PM represents only his/her constituency and the party he/she leads, not the majority of the people. The logical liberal-democratic stand would be a balance of power between the President and the PM, with a decisive edge for the Presidency (as in France) because it represents a majority of the citizen-voters.

If the 13th amendment is deleted or downsized and that counter-reform generates external pressure, such pressure will aim to resurrect the 13th amendment because there is no legitimate basis and consensus, internationally and regionally, to go beyond it. The UN resolutions say “implementation of the 13th amendment”

Tamil political paradigm

If one faction within the drafting committee has argued for the abolition of the system of Provincial Councils, i.e., the 13th amendment, even if there is a compromise, it is likely to be one that reduces the powers of that system. The window is fast closing for any political or politico-diplomatic struggle to defend and retain provincial semi-autonomy.

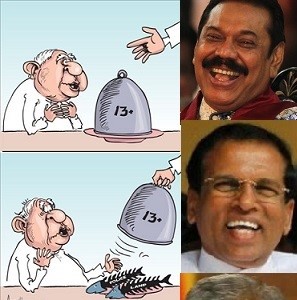

The system of Provincial Councils received only tepid support from the Tamil nationalist mainstream. At the time of its appearance, only the leftwing EPRLF came forward to contest the PC elections. Currently, Gajendrakumar Ponnambalam, MP, is riding with a convoy of vehicles carrying the figure 13 with a X running through it… He makes whistle stop addresses to the media, denouncing the 13th amendment for its accommodation to/within a unitary state—and those Tamil parties that stand for its implementation. The Sunday story should please him.

The TNA’s Sumanthiran who filibustered during the initiative of a letter to Prime Minister Modi seeking his support to uphold the 13th amendment, should be only slightly less glad.

The explicit argument of these immoderate moderates has been that “the Tamil community didn’t lose so many lives to settle for the 13th amendment.” The truth is that having lost so many lives, when the smoke cleared, all that remained was the 13th amendment and the system of provincial councils. By trashing it, or trying to leap over that durable residue and push for a new, non-unitary Constitution, the Tamil nationalists have left the 13th amendment and the PC system utterly unguarded; open to abolition by a Sinhala ultranationalist regime they helped bring about by their rejectionist and maximalist political provocations (as Hamas helped elect Netanyahu).

The real risk is that the lives sacrificed by the Tamil people will have absolutely nothing left to show politically, on the ground, on the island. Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness never left a zero-balance sheet politically for Northern Ireland’s Irish Catholic minority.

The 13th amendment was the product of the Tamil struggle at its zenith, quite contrary to the myth that the Tamil struggle was at its height when Prabhakaran and the LTTE were fighting a spectacular yet solitary war.

The Tamil cause was politically strongest in the 1980s, and the 13th amendment was the product of that favourable balance of forces. In the 1980s, the Tamil struggle was waged by an array of militant organisations. India supported the struggle, though not its secessionist objective. The USA and the USSR deferred to India. In the aftermath of Black July 1983, the Sri Lankan state occupied the moral low-ground.

The Tamil cause never had such broad support ever again nor such powerful support from India. The Sri Lankan state was never so morally-ethically discredited and on the defensive again. In the south of the country, a civil war was fought and won, among other things in support of provincial devolution within a unitary state. What was obtained, was what was obtainable: the Indo-Lanka accord, the 13th amendment and the system of Provincial Councils within a unitary framework.

The LTTE’s spectacular military performance of the 1990s and in the new century and Millennium lacked that breadth and depth of strategic support. The Final War for Tamil Eelam was waged on politically thin ice. The only external support was the Tamil Diaspora. It ended with the (supposedly) invincible Tigers being outfought and beaten in their (supposedly) impenetrable redoubt of the Wanni jungles by soldiers from Sinhala peasant families, before being funnelled into, trapped and eliminated in the killing box. As any real genius of irregular warfare (Mao, Giap) knew—unlike Prabhakaran—if you get your politics wrong, you cannot get your war strategically right.

The ITAK/TNA keeps denouncing successive Sinhala leaderships for not ‘building upon’ and/or “going beyond” the 13th amendment, but it was precisely in the Tamil interest—not so much that of the Sinhalese—to make the 13th amendment work so as to “build upon it” and “go beyond it”. That was primarily the responsibility of the Tamil leadership. Why didn’t it do so, as the Sinn Fein so brilliantly did with the Good Friday Agreement and the ensuing devolved structures?

The answer is that mainline Tamil nationalism (but not so much the non-LTTE ex-guerrilla groups) thought/thinks as follows:

(a) The Tamils could do without India because it had more powerful friends in the West who would come through someday soon.

(b) The 13th amendment was an obstacle to federalism and self-determination.

(c) Having lost the war, international accountability for war crimes was more important than defending, entrenching and reanimating devolution/autonomy.

There was no accountability clause in the Good Friday Agreement. Accountability appeared later, as a byproduct, on the sidelines of an evolutionary process of rising consciousness.

Some personalities succeeded in including ‘federalism’ and ‘self-determination’ in the significant collective letter to Prime Minister Modi. Even the Tamil parties outside the north and east and the Muslim parties in the north and east could not subscribe to that platform.

Which Southern party which aspires to succeed the zero-devolution GR regime, can commit to anything beyond the 13th amendment and its implementation, and survive electorally?

The TNA, and earlier the TULF, pushed their Sinhala allies, President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe beyond the 13th amendment to a commitment to a new quasi-federal Constitution, and both were terminally damaged as a result, with Mahinda and later Gotabaya as beneficiaries.

Any battle for federalism, north-east merger and/or self-determination will have to be waged by the Northern Tamil parties alone. However, a battle for the 13th amendment and the system of Provincial Councils can gather the support of considerable segments of the Opposition.

The permanent hyper-inflationary spiral in Tamil political discourse is not only due to dogmatism but also to internecine competition between and within Tamil political parties. Tamil politics is driven by the dynamics of secession and succession; more succession than secession. Secessionism in the Tamil Diaspora is leveraged by contenders for succession in Tamil politics on the island, while the secessionists in the Diaspora also patronise and manipulate those contenders for succession.

The most powerful drive for self-determination in Tamil politics today is the determination to make oneself the successor to Sampanthan. A leading contender invokes Uncle Sam (claiming Washington will drive a political solution beyond 13A) to position himself as successor to “Sam” (Sampanthan).

Let alone constitutional change, if the electoral reforms in the pipeline are enacted, the number of Tamil politicians in the legislature will be the lowest in decades.

If the 13th amendment is deleted or downsized and that counter-reform generates external pressure, such pressure will aim to resurrect the 13th amendment because there is no legitimate basis and consensus, internationally and regionally, to go beyond it. The UN resolutions say “implementation of the 13th amendment”.

Tamil politicians have perhaps only days to embark upon a prudent, pragmatic and purely defensive strategy in support of 13A, with the broadest possible alliances, Tamil, Muslim and Sinhala.

Strategic economic integration of Sri Lanka with India, i.e., permanent strategic economic dependency, is an enormously flawed idea

13A swap for dependent integration

Could India be tempted to let the 13th amendment go, in a swap for a strategic economic foothold? The Gotabaya gambit is signalled in the interview given to Sri Lanka hand Nirupama Subramanian of the Indian Express by High Commissioner Moragoda. He says, “I think President Rajapaksa wants the two countries to come together, he wants the two economies to integrate more.” (Daily FT)

Moragoda elaborated in an address to the Vivekananda Foundation, the founder-director of which is India’s NSA Ajith Doval and present director is ex-Deputy NSA Dr. Gupta: “…he stressed the need to integrate the Trincomalee Oil Tank Farms and the Port of Trincomalee to the overall energy strategy of India…” (Daily FT)

Strategic economic integration of Sri Lanka with India, i.e., permanent strategic economic dependency, is an enormously flawed idea. India’s sage Chanakya, a.k.a Kautilya says in the Arthashasthra that a state by virtue of its shared or proximate border is bound to have a conflict of interests with its neighbour, which therefore constitutes the source or direction of the greatest threat, and should be balanced-off by tilting to the neighbour’s neighbour.

While such classic geo-strategic axioms need not overly circumscribe Sri Lanka’s omnidirectional options, they tend to prove objectively parametric over the long term. Therefore, a vital distinction must be drawn between (a) exploring greater economic synergies with India through multiple though selective linkages and expansion of shared economic space and congruent interests, and (b) “integration” of Sri Lanka’s economy with India’s. The latter brings to mind the integration of a sprat with a shark or a minnow with a whale. Moragoda wants Sri Lanka to play Puerto Rico to India’s USA.

Sri Lanka’s long-term existential interests of optimising sovereignty and strategic autonomy are far better served by a multipolar diversification of dependence.

Nirupama Subramanian pointedly queried about the 13th amendment. In response, Moragoda, who was as close to former Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe as he is to President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, never mentioned the Indo-Sri, the 13th amendment, devolution, a political solution or the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord. As did President GR in his recent address to parliament, Moragoda stressed ‘development’ instead, flatly asserting that “…in the north and the east, people are not interested in constitutions.” Presumably, the Tamil people aren’t interested in whether or not the 13th amendment/provincial devolution is in this, or any successor Constitution.

Can Ranil give sensible counsel on either an economic policy that can last two terms or ensuring policy continuity by winning two consecutive terms, when he was never re-elected for a second consecutive term, there were 15 years in-between his premierships, and his second term ended with his party’s electoral extermination?

Ranil raps ‘rot’

Ex-Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe rolled-out his economic wisdom at the Rotary Club of Colombo West. The stark contrast between his precept and his practice is staggering.

He advocates a ‘long-term national plan’, but didn’t it start while PM in 2001 and 2015.

In January 2016, Nobel Prize winner in Economic Sciences, former Vice-President and Chief Economist of the World Bank and former Chairman of the US President’s Council of Economic Advisors, Prof Joseph Stiglitz, visited Yahapalanaya Sri Lanka. On a panel with Prime Minister Wickremesinghe, Stiglitz enthusiastically stressed socioeconomic policy priorities for ‘Sri Lanka’s Rebirth’ in the ‘post-conflict’ period. (Sri Lanka’s Rebirth by Joseph E. Stiglitz – Project Syndicate (columbia.edu))

Included in the 2011 TIME magazine’s Top 100 influential people, Stiglitz had zero-influence on Ranil and his economic team. Instead, they turned to neoliberal ‘shock therapy’ guru Ricardo Hausmann. Hausmann notoriously drafted the policy platform of Venezuela’s presidential pretender, Trumpian Trojan horse and far-right flop Juan Guaido. South America’s finance ministers who shared Hausmann’s socially polarizing policy perspective have triggered “A string of victories for progressives in Latin America…Since 2018, left-of-center candidates have won presidential elections in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Mexico, and Peru, and leftists lead in the polls in this year’s campaigns in Brazil and Colombia.” (Foreign Policy, Jan 31, 2022)

Prime Minister Wickremesinghe pulled the plug on all Chinese projects including the Port City; Western investment didn’t flow; the Central Bank Bond scam was a drain of inestimable magnitude and duration on the economy according to the (then) Auditor-General Gamini Wijesinghe; the growth-rate dropped; the bills piled-up; he borrowed more externally than Mahinda Rajapaksa ever did with very much less to show for it; and coughed-up more real estate in Hambantota to the Chinese than Mahinda had done, thereby triggering a spiral of countervailing demands for economic real-estate from India and the USA, creating the dependency trap we are now caught in.

Wickremesinghe correctly situates the contemporary crisis: “Economically, we have not seen such a situation since 1988, 1989”. Sri Lanka exited that crisis and recovered spectacularly through a vibrant new economic model, a Rooseveltian New Deal variant of the Open Economy, instituted by President Premadasa. Prime Minister Wickremesinghe didn’t retrieve that model on the two occasions he was in charge of economic policy, 2001-4 and 2015-2019. As Prof Howard Nicholas underscored last December, industrialisation is the only way out of the Sri Lankan crisis, President Premadasa was the only one who took that path, and “I don’t think Ranil followed it…”

Today, Ranil says “…we have to realise that anyone who is saying that I will do it in one term is talking rot.” President Premadasa did it in under half a term!

Can Ranil give sensible counsel on either an economic policy that can last two terms or ensuring policy continuity by winning two consecutive terms, when he was never re-elected for a second consecutive term, there were 15 years in-between his premierships, and his second term ended with his party’s electoral extermination?

Ronnie de Mel, architect of the Open Economy of 1977, said last year that “the only hope” he sees for Sri Lanka in this crisis is Sajith Premadasa and “getting the whole thing under the control of your [Sajith’s] policies”. Opposition leader Premadasa’s discourse parallels Joe Stiglitz’ policy direction for ‘Sri Lanka’s Rebirth’.