Sharine Silva, a hair and makeup artist in Colombo, has been struggling to make ends meet as costs of essential items skyrocket in Sri Lanka, which has been facing one of its worst economic crises in recent decades.

“There’s no fresh milk or milk powder for tea. Prices for baby milk formula are exorbitant,” said Silva, a mother of two.

“It feels like a war where we have to ration our foods now. That sounds so silly given this day and age,” she added.

Skyrocketing inflation, weak government finances, ill-timed tax cuts and the Covid-19 pandemic, which hurt the important revenue-generating tourism industry and foreign remittances, have wreaked havoc on the Sri Lankan economy over the past several months.

Prices of food items, for instance, shot up by as much as 25% in the last month alone.

Shortage of food and fuel

Meanwhile, the nation’s foreign currency reserves plummeted by about 70% since January 2020 to around $2.3 billion (€2.1 billion) by February, even as it faces debt payments of about $4 billion through the rest of the year.

Sri Lanka’s current reserves are only enough to pay for about a month’s worth of goods imports.

A shortage of foreign currency has meant that the country has been struggling to import and pay for essential commodities like fuel, food and medicines.

These challenges has led to cuts in electricity generation, with only four hours of power a day, and long queues outside fuel stations.

Even the newspaper and printing industries have been hit by a severe shortage of printing material, forcing cuts in publications and school examination postponements.

Prasad Welikumbura, a social and political activist in Sri Lanka, said it’s the daily-wage earners who’ve borne the brunt of the crisis.

“It’s really hard for people like taxi drivers and tuk-tuk drivers,” Welikumbura told DW.

The economic pain has caused growing anxiety and frustration among Sri Lankans, with many of them blaming the government of mismanaging the economy.

Tax cuts and pressure on public finances

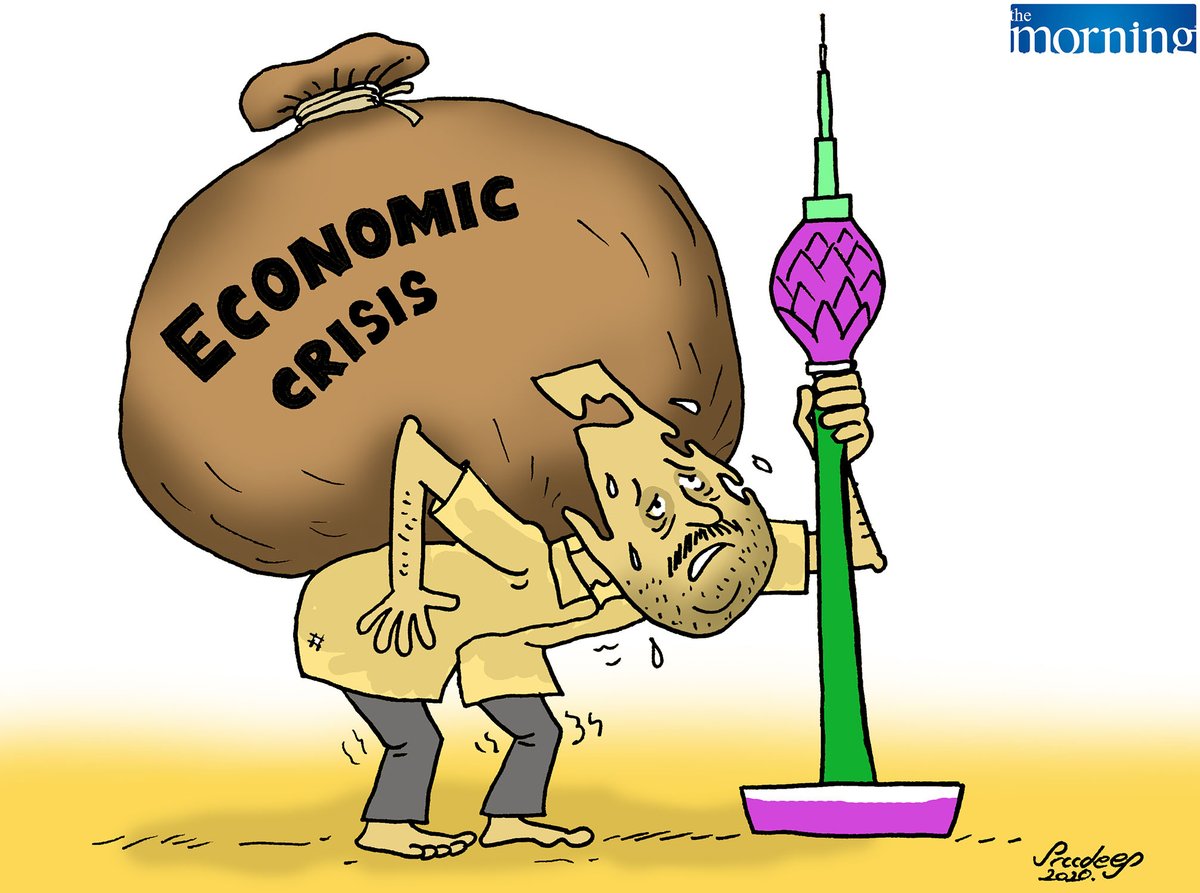

The economic emergency poses a significant challenge for President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who came to power in 2019 promising rapid economic growth.

During his presidential campaign, Rajapaksa promised to cut the 15% value-added tax by nearly half and abolish some other taxes as a way to boost consumption and growth.

The tax cuts led to a loss of billions of rupees in tax revenues, putting further pressure on the public finances of the already heavily indebted economy.

Then came COVID, which dealt a huge blow to the tourism sector, which accounts for over 12% of the nation’s total economic output.

Sri Lanka’s public debt, which was already on an unsustainable path before the pandemic, is estimated to have risen from 94% in 2019 to 119% of GDP in 2021.

“The reduction of taxes and subsequent adding of more money through central bank financing made the inevitable crisis significantly worse,” said Chayu Damsinghe, an economist with Frontier Research group.

India, China and IMF to the rescue?

To address the economic problems, Rajapaksa’s government has restricted imports of several items which have been declared “non-essential.”

It has also approached India and China for assistance.

It’s reported on Monday that Colombo has sought an additional credit line of $1 billion from India to import essential items, after Sri Lankan Finance Minister Basil Rajapaksa signed a $1 billion credit line with New Delhi earlier this month.

In addition to the credit lines, India extended a $400-million currency swap and a $500-million credit line for fuel purchases to Sri Lanka earlier this year.

Meanwhile, Sri Lanka has asked China to restructure its debt repayments to help navigate the financial crisis. The country is also in talks with China for a further $2.5 billion in credit support.

Despite the bilateral deals, economists say Sri Lanka will have to either restructure its debt or approach the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to negotiate a relief package.

After initially refusing to knock on the doors of the IMF, Rajapaksa’s government recently said it would begin talks with the global financial situation to seek a way out of the crisis. Rajapaksa is set to fly to Washington, D.C. next month to start negotiations for a rescue plan.