The passage of the 22nd Amendment to the Constitution (22A) cannot be considered a personal achievement of any individual politician. It was born out of a collective effort. Most of those who voted for the 22A Bill acted out of expediency rather than principle. Among those who backed it are some ardent supporters of the executive presidency. They voted for the 18th and 20th Amendments in 2010 and 2020 respectively to strengthen that institution. It was to settle political scores with their bete noire, Basil Rajapaksa, that they backed the 22A Bill overwhelmingly on Friday.

The problem with Sri Lanka’s supreme law as well as most amendments thereto is that they have been tailor-made to meet the needs of some power-hungry political leaders. The Constitution itself was created to enable J. R. Jayewardene to satiate his thirst for unbridled executive powers. His mighty hurry to introduce the presidential system resulted in numerous flaws in the Constitution, which we have had to live with.

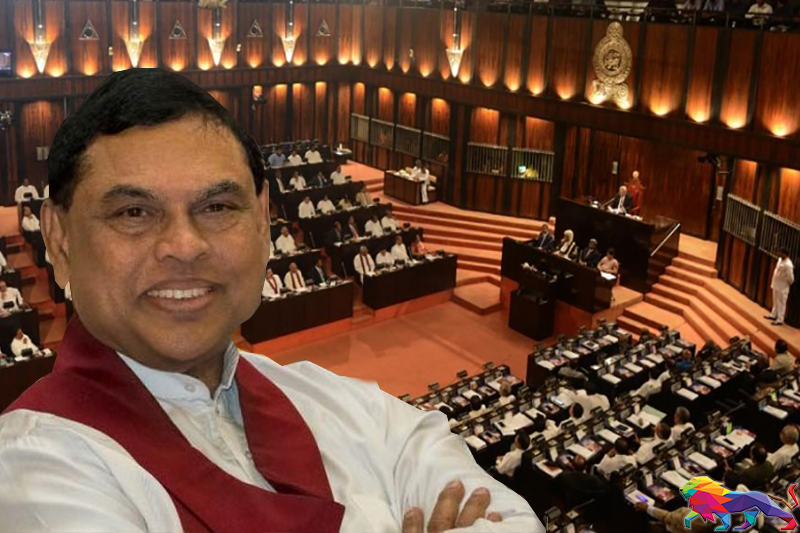

The 13th Amendment, made in India, sought to solve Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s problems in Tamil Nadu rather than Sri Lanka’s ethnic issue. The 18th Amendment, made in Medamulana, helped President Mahinda Rajapaksa become a king in all but name. The 20th Amendment restored the executive powers of the President for the benefit of Gotabaya Rajapaksa. Only the 17th and 19th Amendments, introduced in 2001 and 2015 respectively, could be considered pro-people, but the latter unfortunately smacked of a move to further the interests of the then Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe and place the Rajapaksa family at a disadvantage. The 22A also contains a section aimed at keeping Basil at bay; it has disqualified dual citizens from entering Parliament.

President Ranil Wickremesinghe has been praised in some quarters for the passage of 22A, which reduces his presidential powers, but he has only made a virtue of necessity. It was drafted on President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s watch. President Wickremesinghe has neither gained nor lost anything significant due to 22A. He promised consensual governance and undertook to strengthen the independent commissions. He would not have been able to exercise the powers that the executive presidency has now been stripped of. With only a single MP on his side, he cannot do anything without the concurrence of the SLPP, which controls Parliament.

The outcome of Friday’s vote in Parliament could be thought to indicate the emergence of another dissident group in the SLPP with some more ruling party MPs apparently becoming responsive to public opinion, which is not in favour of the government. Basil has the habit of making himself scarce whenever things go wrong for his family and party. He rushed to the US after the 2015 regime change. He would have left the country last July as well but for protests at the BIA. He can always run away to the US, where he is safe. But most SLPP MPs cannot do so; they have to be here facing the people’s wrath.

Interestingly, even some members of the Rajapaksa family—Chamal, Namal and Shasheendra—voted for the 22A Bill; in so doing, they endorsed the ban on dual citizens like Basil from entering Parliament! Maybe they are running with the hare and hunting with the hounds.

It is said that Basil may renounce his US citizenship and re-enter Parliament. But it is doubtful whether he will take such a gamble, having witnessed the predicament of his brother, Gotabaya, a former US citizen, who tried to migrate to the US after his ouster, in July, only to be denied a visa. Finally, he had to take refuge in Thailand, of all places, before returning home. What the passage of 22A signifies is that President Wickremesinghe and the SLPP can extricate themselves from the Rajapaksas’ clutches, serve the interests of the people and perhaps even regain public support, if they pluck up the courage to do what is right and enlist the backing of the Opposition.