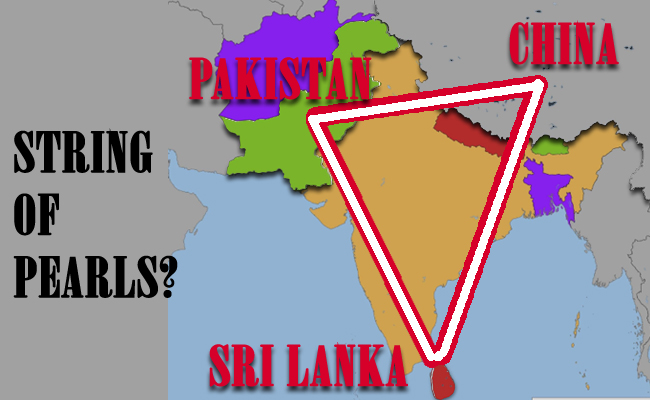

Former Indian Foreign Secretary, Shivshankar Menon has said that although China has invested heavily in countries like Pakistan and Sri Lanka, that does not automatically translate into political influence over a country’s foreign policy, popularity, or into soft power.

He said this responding to a question on the role of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) plays in advancing China’s economic and soft power interests in South Asia during an interview with E-International Relations magazine.

“The BRI plays a very considerable role in advancing China’s interests. It plays to China’s strengths, which are economic, where it is not really matched by any other power in the subcontinent. Nor do outside powers prioritise countervailing China’s growing influence in the subcontinent. By committing over US$ 100 billion to BRI projects in the subcontinent, China has made herself indispensable to the infrastructure and economic plans of the leaders of several countries in the subcontinent,” he said.

However, at the same time the examples of Pakistan and Sri Lanka suggest that one should be cautious in drawing the conclusion that this automatically translates into political influence over a country’s foreign policy, popularity, or into soft power, he said.

“The attractiveness of the Chinese model or way of doing things is still rather limited, as is their power of attraction. This is still a work in progress and the Chinese leadership has often spoken of the need for China to gain soft power. So, its impact on India’s relations with these countries has not, to my mind, yet peaked. India has other affinities and common interests with our neighbours that China cannot match that I think we should concentrate on, rather than trying to match or imitate China,” he said.

Menon added that in his recent book ‘India and Asian Geopolitics: The Past, Present‘, he suggests that China will not behave as Western powers have. He said that the Chinese are very conscious of their own political and strategic tradition. China, particularly their present leadership, see the last 150 years as a historical aberration, a “century of humiliation,” Menon said.

“It is an aberration in their mind from an imagined past when China was the preeminent power in the world, the largest economy, a technological leader, and so on. Objective historians and non-Chinese might have their own, different view of the past, but it is this perspective and the quest for primacy it produces that seems to drive China’s international behaviour now,” he said.

China’s is a different strategic culture from that of the two previous global superpowers, Great Britain and the USA, he said. The former Indian Foreign Secretary said that China’s geography, history, resource endowment and dependencies on the world are different from those western powers.

“Hence my sense is that they will not behave as western powers have. Today, China is yet to be a global superpower, and it is difficult to predict whether she will succeed in this quest, which is facing resistance,” he said.

Menon also said that if the political relationship between China and India remains adversarial, cutting their economic dependencies on China would become a strategic necessity.

“To my mind, the two countries need to find a new paradigm for the relationship, or a new strategic framework, within which to manage or settle these issues and to take the relationship forward. In other words, the present situation calls for a fundamental reset of India-China relations,” he said.

He added that the biggest challenge for India in the last decade was the fact that the international environment became less supportive of the efforts to transform India, particularly after the global economic crisis that began in 2007-8.

“The rise of China and the growth of China-US strategic rivalry changed the situation, opening new opportunities for India-US relations but also creating challenges in our neighbourhood and on the India-China border where China has been changing the status quo. China has emerged unequivocally as our greatest strategic challenge but is also our greatest trading partner. We now face a complex set of relationships with all our neighbours and the major powers in a world that is adrift between orders,” Menon said.

Menon also said that the idea of hard linear boundaries is a relatively recent one in history, a feature of the Westphalian state that has acquired popular legitimacy with the rise of nationalism. However, South Asia has “old nations in new states” he said, pointing to the limitations of these boundaries.

“For most of history, borders, as opposed to linear boundaries, were zones of interaction and communities straddled these borders, while trading, traveling, and carrying on the normal business of life across these porous borders.

With the evolution of India and its neighbours into modern Westphalian states in the second half of the 21st century, and the partitioning of the subcontinent into post-colonial states, hard boundaries were imposed on ancient communities and nations which did not coincide with natural features or ethnic divisions or with their patterns of life.

This is why border zones in most of our countries have been unstable and increasingly securitised by the state, with unfortunate consequences for the inhabitants. The most extreme example of this phenomenon is Pakistan. But I do believe that there are political and economic solutions to these issues which are increasingly being practised by the other countries in the subcontinent, such as India and Bangladesh,” he said.