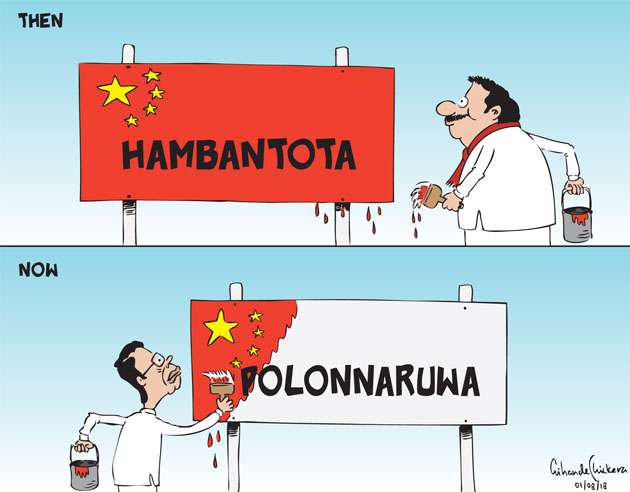

The road to Hambantota may be paved with Chinese money, but its value is up for debate — now more than ever.

Set among the soft, green rice paddies and coconut palms of Sri Lanka’s deep south, Hambantota is best known as the stronghold of the nation’s Rajapaksa clan, who have spent years using borrowed money to build monuments to themselves. The little-used Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport, the often overgrown Mahinda Rajapaksa Stadium, and a memorial to the Rajapaksa elders that was burned and destroyed by a furious crowd of protesters on May 9, are testament to that terrible waste.

A statue commemorating D.A. Rakapaksa — a former member of parliament and father of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa and the recently resigned prime minister, Mahinda — was also targeted. It now lies on the ground, covered in a tattered piece of orange tarpaulin — another symbol of citizens’ anger against the family. The clocktower in the center of their home town of Weeraketiya has been vandalized, “Gota Go Home” spray-painted on its sides. Until now, it would have been unimaginable to see this sentiment expressed in the Rajapaksa heartland. While some locals say the infrastructure projects have created jobs, others vow they will no longer stand for what they see as such obvious misuse of public funds.

Less than 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) away, local farmers and traders are preparing for the worst. The president’s decision to flick the switch to organic farming overnight by banning chemical fertilizer imports in May last year caught everyone by surprise, and irrevocably harmed those in the agriculture sector in the family bastion. The ban was lifted six months later, but by then, the damage was done — yields were decimated and the country had plunged into a food and foreign reserve crisis that ended with its default on May 19.

“He destroyed his own village with that decision,” says cinnamon farmer and local opposition politician, Anura Vidana Arichi, gesturing to the rice paddies just beyond his house. “These fields have been cultivated for decades — yields have fallen more than 50% this season and we have abandoned the farming for now. Next season only 10% will be planted, and even then we don’t know what will grow without fertilizer.”

As inflation neared 40% last week, the government urged farmers to start planting rice. No matter. This attempt to stave off a an ever deeper food crisis will likely have little effect — there is no money to import fertilizer and without it, the crops just won’t produce anything close to what’s needed to feed the island’s 22 million people. Wickremesinghe has warned of an acute food shortage by September, while the president has asked officials to start stockpiling essentials in preparation.

The South Asian nation needs as much as $4 billion to see it through its worst economic crisis since it gained independence from Britain in 1948. Negotiations with the International Monetary Fund and key bilateral creditors, China, Japan and India, are ongoing. But it is going to take a lot to unpick its tens of billions in foreign debt and the tangled web of capital market borrowings and Chinese loans for those unprofitable infrastructure projects. The Rajapaksa government’s decision in 2019 to cut taxes, especially for the wealthy and corporations, led to annual revenue losses of as much as $2.2 billion. The new regime is looking to reverse that decision in order to meet IMF bailout conditions.

In Colombo, doctors and lawyers have joined together in an unprecedented push to convince the government to undertake real reform, not just constituting committees, as new Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe is famous for. Keeping the hospitals, clinics and courts running will be done at all costs. But forcing politicians to abandon the corrupt practices of the past and rebuild Sri Lanka’s public sector will take more sustained efforts, they say. Like the protesters camped in the capital, they want the president to resign.

An urgent letter sent to the nation’s diplomatic community in April that flagged alarming shortages in the medical supply chain of 273 critical items — from anti-cancer drugs to orthopedic implants and reagents used for blood tests — prompted swift action from embassies and high commissions. Some drug donations arrived and stocks of anesthesia were temporarily replenished, but most elective surgery has been canceled due to the crisis. The juggle to maintain treatment regimes for patients with chronic conditions, as well as deal with emergencies and viral illnesses, particularly as the dengue season kicks in, is intense, say doctors like general practitioner Ruviaz Haniffa and senior physician, Ananda Wijewickrama.

“We have been telling the government since last October they had to requisition these drugs, and by January we’d warned them this was becoming acute,” Haniffa says. “We cannot run a health system on donations alone.” Former Maldives President Mohamed Nasheed, who was appointed last month to coordinate relief efforts, is also leading the global appeal for urgently needed medical supplies, Wickremesinghe said June 3.

Is it any wonder people are angry at what they have lost? They have seen the politicians’ mansions and luxury cars and all those wasted billions — and now they are feeling the pain of default in every aspect of their lives. (A court case, in which the president was indicted over the misappropriation of 33 million rupees ($91,000) in public funds to build the museum to his parents, was dropped soon after his election in November 2019. There are other serious allegations against the family and their associates, including money laundering, the illegal transfer of state-owned weapons worth millions and a separate case of mismanagement and corruption at Sri Lankan Airlines. The brothers deny all corruption claims.)