The schoolgirl

Krishanthi Kumaraswamy cycles along a dusty road in the sweltering afternoon heat of Jaffna. ‘Ubiquitous palms, unique to the dry zone, stand direct like sentinels. An eerie feeling permeates the scenery and vegetation in this no-man’s land’. She was on her way to her Chemistry Advanced Level exam. She would be home for lunch. Home was her haven, the place that cushioned her from the war that she had known almost all her life – the place she shared with her widowed mother and younger brother.

Krishanthi was a high achiever. She had aced her O’Levels with seven distinctions and she knew that she was going to blitz the A’Levels as well. She had to. She wanted to study Medicine at University, a very competitive and demanding course. One that only a handful of elite Jaffna students could get into.

Krishanthi never arrived home! Her A’Level results were posted posthumously. She had passed with the highest possible grades, but she wasn’t there to celebrate the news! The 18 year old had been raped and killed by army personnel who had stopped her at a checkpoint on her way home, ostensibly to question her.

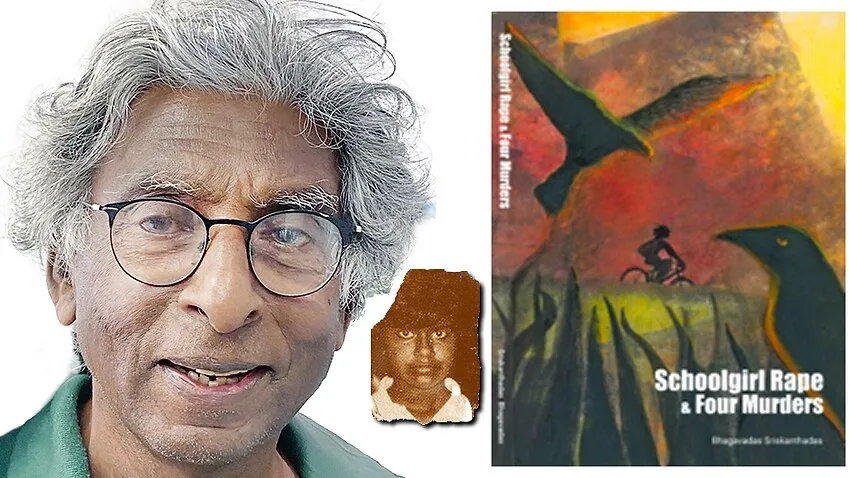

The book

Krishanthi remains the face of the horrors of the thirty year civil war in Sri Lanka and the tragic victim of the militarisation of the North. The rape and murder of the schoolgirl by the army and the murder of her mother, brother and neighbour who went looking for her in September 1996, has been graphically captured in a book written by Bhagavadas Sriskanthadas ‘Schoolgirl Rape & Four Murders’. It follows the crime through the court case and the proceedings some of which are produced ad verbatim in the book and provide first- hand accounts of what transpired.

The book was launched at Gleebooks in Sydney on 5 June 2022. Speaking at the launch, Sriskanthadas a former human rights lawyer, journalist and solicitor at the Aboriginal Legal Service in Australia, described the atrocities of war and rape in particular, as a weapon of war. He listed Rwanda, the Congo, Yugoslavia and more recently, Ukraine as countries where rape was systemic during conflict. In his foreword he also describes the many human rights violations committed during the war in Sri Lanka and the absence of any Governmental measures to curb the military or hold them accountable for the atrocities they committed.

Sriskanthadas writes with the clinical accuracy of someone who had poured over the court proceedings and researched conditions in Jaffna during the war, but writes with the heart of someone who understands and appreciates the Tamil culture and ethos. He travelled to Kaithady, Jaffna, where he interviewed neighbours, relatives and friends of the Kumaraswamy family while compiling the book.

Life in the North

Peppered through the book are cameos of life in the North which are familiar to someone who has grown up there – bicycles (a common mode of transport in Jaffna) and the history behind them, the meaning of the Thali Kodi for a Hindu wife, Saraswathi, the Goddess of Learning and Krishanthi’s affinity to her… Sriskanthadas’ powers of observation are heightened by his knowledge of Tamil culture and history.

While the burden of war was punishing, the people continued with their daily rituals and routines – their attempts to maintain normalcy in an otherwise abnormal environment. A review of the book by Philip Radmall, Macquarie University, says that ‘it speaks from the precariousness of ordinary life; how randomly the horror of the killings takes place out of the domestic context and routine goals of a day’. Sriskanthadas captures those routine moments with great detail and warmth.

Against this backdrop, Krishanthi’s personality and family life come alive.

What is distinct in the book is that the Kumaraswamy family were well respected people in the area – cosmopolitan, educated and influential. Krishanthi’s mother grew up in Malaya and did a Bachelor of Arts in India, returning to serve as Principal at a public school in Jaffna. Both younger children were in the best fee paying schools in Jaffna (the oldest daughter was in Colombo). Arguably, they had some power and influence and their family members were able to get the then President of the country, Chandrika Kumaratunga to intervene and justice was served in a fairly quick trial without jury.

The State Counsel for the prosecution in the Kumaraswamy case said in an interview, “In March or April of 1997 the case started and in 1998 it was over. Krishanthi Kumaraswamy was the first successful prosecution against military personnel for rape in the context of the conflict in Sri Lanka”. A pyrrhic victory for the Kumaraswamy family, who lost three members of their family in a senseless act of violence.

The political narrative

While the story is about Krishanthi and the subsequent court case and victory, running through the book is a political narrative that speaks of an ineffectual Government and a country with a tainted human rights record… A country that abandoned its duty towards its people in the North and East and its humanitarian obligations towards them.

Jaffna was wrested from the terrorists in December 1995 and supposedly in the safekeeping of the army. The irony is not lost on the young girl as she is shoved into the army bunker ostensibly for questioning, but in reality for a far more sinister purpose. “We trusted you and we came”, she tells the army corporal. The so-called saviours, the perpetrators of crimes against humanity!

The previous year, the UN’s Fourth World Conference on Women specified that rape by armed groups during wartime is a war crime. ‘The jurisdiction of the international tribunals established to prosecute crimes committed in the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda both included rape, making these tribunals among the first international bodies to prosecute sexual violence as a war crime’.

The UN and human rights groups have pressed Sri Lanka to set up a war crimes tribunal, a request that Colombo has resisted saying it is an internal matter and would be dealt with internally. So many women have been raped, tortured and murdered in Jaffna during the occupation by the armed forces with complete impunity. Their tragedy is just a line item in statistics compiled by human rights organisations.

In March 2000, the UN special rapporteur on violence against women expressed grave concern over the lack of credible investigations into allegations of gang rape, and murder of women and girls. In a January 2002 report Amnesty International noted that not a single member of the security forces had been brought to trial in connection with incidents of rape in custody.

A tribute

Krishanthi’s rape and murder and the murder of her family rocked Jaffna, but for every Krishanthi whose body is recovered and whose story is told, there are a thousand Krishanthis who will remain unknown and unmourned, except by their close families. Jaffna keeps some dark secrets and the book lifts the veil on one of them.

The author concedes that people may question the relevance of the book and the fact that it had been written 20 years after the event – it is a seminal case which was prosecuted successfully, (despite the evidence being largely circumstantial), but one that is sadly not representative of the outcome of many rapes, abductions and killings by the military in the North and East.

Bhagavadas Sriskanthadas’ book is not just a tribute to a Jaffna schoolgirl with a dream who never came home, but it is also a tribute to all those women in the North and East who will never come home to their families.