The current disturbance in India-Sri Lanka relations caused by the proposed docking of the sophisticated Chinese military survey vessel Yuan Wang 5 at Hambantota port is but the latest in a long series of hiccups in Indo-Lankan strategic relations.

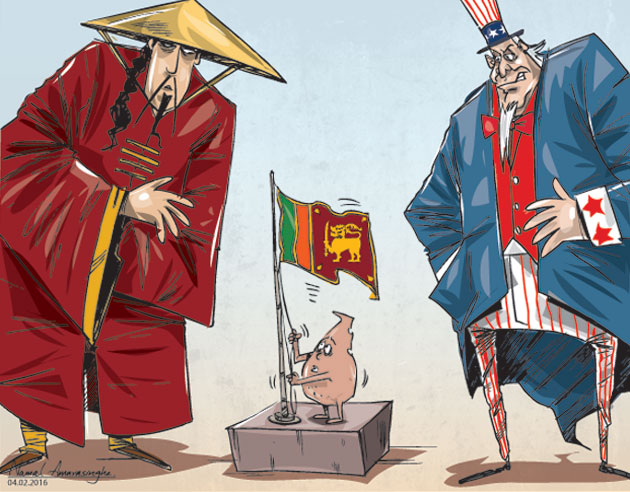

The relationship has been seeing ups and downs since the two countries became independent in the 1940s. A factor characterizing the relationship is the difference in the strategic vision of the two countries. India has consistently believed that Sri Lanka is vital for its security in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR), and that the island must be within its political and defense perimeter. In contrast, Sri Lanka has consistently labored under fear of Indian domination or even absorption due to the asymmetry in power, physical proximity, historical links, and ethnic and religious commonalities.

While India has attempted to block the influence of powers thought to be inimical to it, Sri Lanka has cultivated India’s rivals to use them as a check on India’s dominance. The India-Sri Lanka spat over the proposed visit of Yuan Wang 5 to Hambantota stems from the contradiction between these two tendencies.

According to Punsara Amarasinghe, author of a paper entitled “Small State Dilemma” (Open Military Studies 2020), a Lankan leader had said that “the day Ceylon (Sri Lanka) dispensed with Englishmen completely, the island would go under India.” Lankans were disconcerted by Indian scholar-diplomat K.M Panikkar’s 1945 thesis that cooperation between India, Burma and Sri Lanka would be “a pre-requisite for a realistic policy of Indian defense.” He wrote: “The first and primary consideration is that both Burma and Ceylon must form with India a basic federation for mutual defense whether they will it or not. It is necessary for their own security.”

Additionally, according to Amarasinghe: “ Many Indian policymakers and strategists believed that the departure of British power from the Indian Ocean region had enthroned newly independent India as the natural successor to Britain as the guardian of the Indian Ocean.”

In the 1950s, Sri Lanka had declared “neutrality” as its foreign policy. But this was not adequate to appease New Delhi, Amarasinghe avers. An Indian Navy officer Ravi Kaul wrote in 1974: “Sri Lanka is as important strategically to India as Eire is to the United Kingdom or Taiwan to China. As long as Sri Lanka is friendly or neutral, India has nothing to worry about, but if there is any danger of this island falling under the domination of a power hostile to India, India cannot tolerate such a situation endangering her territorial integrity.” More recently, retired Indian National Security Advisor, Shivshankar Menon, described Sri Lanka as a “permanently-stationed aircraft carrier” off the Indian southern coast.

In 1963, Lankan Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike, touched raised the hackles in India when she signed a Maritime Agreement with China. This was a year after China invaded India. India feared that the Sino-Lankan agreement could acquire a military dimension at a time when India’s navy was still a Cinderella. In 1962-63 India expected Sirimavo to support India in its territorial dispute and war with China, but it was not forthcoming. Her only effort was to make them talk.

In 1971, when Sirimavo faced an attempt by the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) to seize power, India sent choppers to help the Lankan forces. But come December 1971, when India needed her support for the liberation war in Bangladesh, she gave refuelling facilities to Pakistan’s military aircraft. India was rubbed on the wrong side.

After Sri Lanka liberalized its economy in 1977-78, President J.R. Jayewardene joined the Western camp, while India’s relations with the US had soured because of the latter’s support for Pakistan in the Bangladesh liberation war in 1971. After the 1983 anti-Tamil riots in Colombo and the influx of Tamil refugees into Tamil Nadu, India began to back the Tamil militants.

But there was an Indian security/geopolitical dimension to the intervention also. Ex-Indian envoy in Colombo J.N.Dixit wrote: “It would be relevant to analyze India’s motivations and actions vis-à-vis Sri Lanka in the larger perspective of the international and regional strategic environment obtained between 1980 and 1984”. Amarasinghe quotes the then Minister of National Security, Lalith Athulathmudali, as saying: “India wanted to control her surroundings. They had an obsession that Trincomalee was being given as a base to the US.”

In mid-1987, India stopped the advance of the Sri Lankan army against the Tamil Tiger militants. It pressured Jayewardene to sign the India-Sri Lanka Accord in July 1987 and accept an Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF). The Accord made Sri Lanka bar forces inimical to India from using its ports and other facilities.

To get even with India, President R.Premadasa armed the Tamil Tigers to help them take on the IPKF. Later, he gave the IPKF an ultimatum to leave. A miffed India refused to give military aid to Colombo when it resumed fighting with the Tigers in June 1990. However, in the final stages of the war in 2007-2009, India helped Colombo defeat the LTTE. A “troika” of top security officials from Delhi and a “troika” from Colombo, facilitated the process.

But there was a change in the Delhi-Colombo security equation with China entering Sri Lanka as a big builder of infrastructure. Among the projects, the deep-water port in Hambantota raised the hackles in New Delhi. In 2010, Alok Kumar and Ishwaraya Balakrishnan said in a paper in the Indian Journal of Political Science: “The construction of this port will bring China within breathing distance of India’s southern coast where sensitive installations, including power plants, are present. It could also help China in keeping a track of India’s nuclear, space and naval establishments in South India and also serving as a listening post”.

India’s apprehensions onIy increased when, in 2017, the port was leased to China for 99 years.

In 2014, a Chinese nuclear submarine “Changzheng 2 had docked in Colombo almost coinciding with the visit of President Xi Jinping. New Delhi saw this as a case of Beijing cocking a snook at New Delhi with Colombo’s connivance. In Indian eyes, the docking violated the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord which stipulated that no port in Sri Lanka will be made available for military use by any country in a manner prejudicial to India’s interests.

But China also has security interests in the Indian Ocean, points out Amarasinghe. Zhao Nanqui, the director of the General Logistics Department of the People’s Liberation Army had said: “We can no longer accept the Indian Ocean as an ocean only for the Indians”. Zhang Ming, a Chinese naval analyst had warned that approximately 244 islands from Indian Nicobar and the Andaman archipelago could be used by India as a metal chain to hinder Chinese ships entering the Strait of Malacca.

When Gotabaya Rajapaksa came to power in 2019, Foreign Secretary Adm. Jayanath Colombage said: “We have to understand the importance of India in the region and we have to understand that Sri Lanka is very much in the maritime and the air security umbrellas of India. We need to benefit from that”.

Indian and Sri Lankan navies have conducted joint exercises nine times under the SLINEX series. Recently, India and Sri Lanka agreed to set up a joint Maritime Rescue Coordination Center (MRCC) with a US$ 6 million grant from India. Sri Lanka would also get a donation of a US$ 19.81 million worth 4,000-ton floating dock, a Dornier surveillance aircraft and a ship repair dock from India.

Sri Lanka became part of India’s Security and Growth for all in the Region (SAGAR) scheme. Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) is part of SAGAR. But in the case of Yuan Wang 5, Sri Lanka had not shared with India, information about its coming. Hence India’s displeasure.