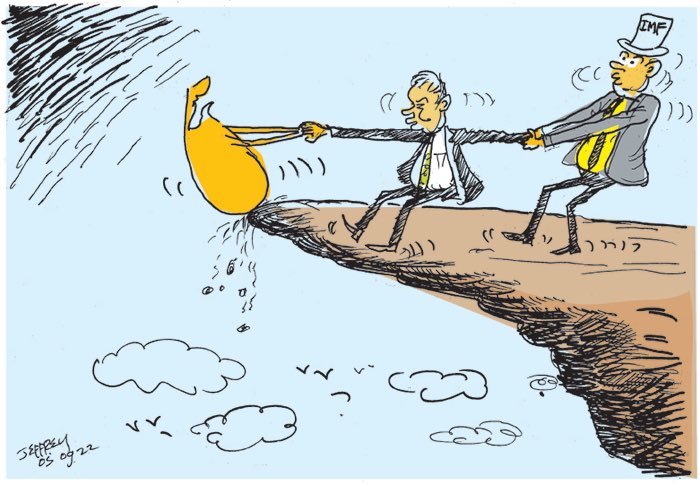

COLOMBO — Sri Lanka is counting the minutes to Monday, when the International Monetary Fund’s executive board is expected to approve a $2.9 billion bailout for the bankrupt island nation.

For the first time in months, many are hopeful that the IMF’s decision will kick-start the country’s recovery from its worst economic crisis since independence from Britain in 1948.

Faced with deepening poverty under high inflation, scarce foreign reserves and dire shortages of essentials, Sri Lanka is on the cusp of the bailout after China offered additional financing “assurances” required by the fund, following months of tough negotiations. Beijing’s apparent hesitance to extend support drew comparisons to a more obliging India. But Sri Lanka’s ambassador to China, Palitha Kohona, strongly defended the country’s key bilateral lender, telling Nikkei Asia, “The Chinese bureaucracy works according to its own rhythm.”

Experts stress just how crucial the final IMF approval is for stabilizing Sri Lanka’s economy, after the turmoil that brought down President Gotabaya Rajapaksa last year.

“Without fresh dollars to import essential goods, an economic turnaround is impossible,” said Sergi Lanau, deputy chief economist at the Washington-based Institute of International Finance. “In the medium term, implementing reforms under the IMF program and successfully restructuring debt should improve Sri Lanka’s outlook.”

In February, the country’s foreign reserves increased to $2.2 billion thanks to various factors such as higher remittances from overseas workers, though the sum is still far from sufficient. Talal Rafi, an economist at the Deloitte Economics Institute, believes that if Sri Lanka receives the IMF loan, it will allow the country to unlock more capital from the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank and bilateral partners.

“IMF approval certifies to the world that Sri Lanka is on the right path,” he said. However, he cautioned, entering an IMF program is “just the beginning.”

The reforms that come next will not be easy. Sri Lanka has gone to the IMF before, completing only nine of 16 such programs. “So, implementing the right reforms is most important, or we would be at the IMF again, like Argentina,” Rafi said.

Dhananath Fernando, chief executive of the independent Advocata Institute policy think tank in Colombo, is skeptical in light of Sri Lanka’s track record. But he is also hopeful because, he said, the severity of the crisis leaves little space to deviate from the program.

“When we went to the IMF during the past 16 times, our debt was sustainable, but this time … our debt is not sustainable,” Fernando said, saying it would be “next to impossible” to deal with those obligations without the IMF. “We need growth and we need to grow out of the crisis, and growth will take place only when we implement economic reforms,” he said.

In focus are Sri Lanka’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs), many of which have racked up huge losses. SriLankan Airlines’ loss in the first half of the 2022-2023 fiscal year came to over 100 billion Sri Lankan rupees ($295 million), more than twice the amount the government spends on support for the most vulnerable citizens.

“Sri Lanka has a bloated public sector, where salaries and pensions took up 86% of government revenue in 2021, and many SOEs are making massive losses and do not even have annual reports for public reference,” Rafi said.

Analysts said that the country needs to redirect more money to the poor, and that SOE reforms are also essential in order to make doing business easier. Sri Lanka is ranked 99th in the World Bank’s index on the ease of doing business.

But Fernando noted that many of Sri Lanka’s leaders have backpedaled away from promised reforms in fear of consequences at the ballot box. “SOEs have been used as a political weapon by most political parties to provide employment for supporters to get more votes,” he said.

While President Ranil Wickremesinghe’s government attempts to put its own house in order, there are lingering questions about the potential geopolitical fallout of the crisis.

India and China, strategic regional competitors and key lenders to Sri Lanka, have been in the spotlight lately. Last week, Sri Lanka asked the State Bank of India and the Indian High Commission in Sri Lanka to extend a $1 billion credit line by half a year beyond the scheduled expiration later this month. Informed sources close to the Indian government told Nikkei Asia that the two sides are discussing the matter.

Last year, India extended around $4 billion worth of support to Colombo. In mid-January, it offered assurances to the IMF that it was willing to support Sri Lanka’s debt restructuring.

China, for its part, was seen as more reluctant to offer a similar pledge. Beijing did send help, but it mostly came in forms other than financial assistance. In 2022, China donated 10,000 tons of rice for more than 1 million students across 7,900 schools, along with 5 billion Sri Lankan rupees’ worth of medicine and health equipment.

But when the Export-Import Bank of China followed India by sending a letter to Sri Lanka’s Finance Ministry in late January, offering a two-year debt moratorium, it was met with disappointment. “China was expected to do more,” Reuters quoted a Sri Lankan source as saying. “This is much less than what is required and expected of them.”

In February, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen criticized Beijing’s approach to distressed countries more broadly, saying, “China’s lack of willingness to comprehensively participate and to move in a timely way has really been a roadblock.”

In early March, the Ex-Im Bank sent another letter, promising to expedite debt treatment and finalize the terms in the coming months. This moved Sri Lanka over the line with the IMF.

George I.H. Cooke, a Sri Lankan former diplomat, stressed that India and China had different priorities. He said a continued collapse in Sri Lanka would have been a bigger immediate problem for India, risking a refugee influx.

On the other hand, Cooke noted that China lends to many countries, and that easily granting concessions could have led to “many others tapping on their doors [saying], ‘Give us the same thing you gave Sri Lanka and help us too.'”

Ambassador Kohona insisted that China has always been helpful, from countering terrorism to supplying COVID-19 vaccines. On debt, the envoy acknowledged that obtaining approvals was time-consuming but said, “We had no doubt that China would take its time but would stand by Sri Lanka in its time of dire financial need.”

He added, “Undoubtedly, we are also grateful that, as major bilateral creditors, India and Japan also have provided the requisite assurances.”