During the past decade, China funded the construction of massive infrastructure projects in Sri Lanka meant to boost the island nation’s economy.

However, after the economic collapse of the tiny Indian Ocean country earlier this year, there were questions whether these projects had contributed to the worst crisis it has ever faced.

A port city that dominates Colombo’s seafront was built on a 269-hectare patch of land reclaimed from the sea. It was to become a thriving business and financial hub, but it is virtually deserted. An international airport commissioned nearly a decade ago at Mattala city is called the “emptiest airport in the world.” Both the Chinese-funded projects are seen as “white elephants” that have added to Sri Lanka’s debt.

“The airport is not functioning. The Colombo port city was supposed to attract international investors, but there is not a single investor right now,” said Asanga Abeyagoonasekera, a Sri Lankan security and geopolitics analyst. “There is a question over the revenue model of all these projects because they are not financially viable. They were built with unsustainable large amounts of borrowings with high interest rates.”

The focus zeroed in on the Chinese projects when Sri Lanka ran out of foreign exchange to import food, fuel and medicines earlier this year. The catastrophic economic downturn has pushed many in the nation of 22 million people into poverty. In what was once a middle-income country, living standards have plummeted as inflation rages. The World Food Program estimates that nearly 6 million people need food assistance.

The country’s crisis is blamed on economic mismanagement by the previous government led by former president Mahinda Rajapaksa and the COVID-19 pandemic that led to a loss of vital tourism earnings in the scenic Indian Ocean country.

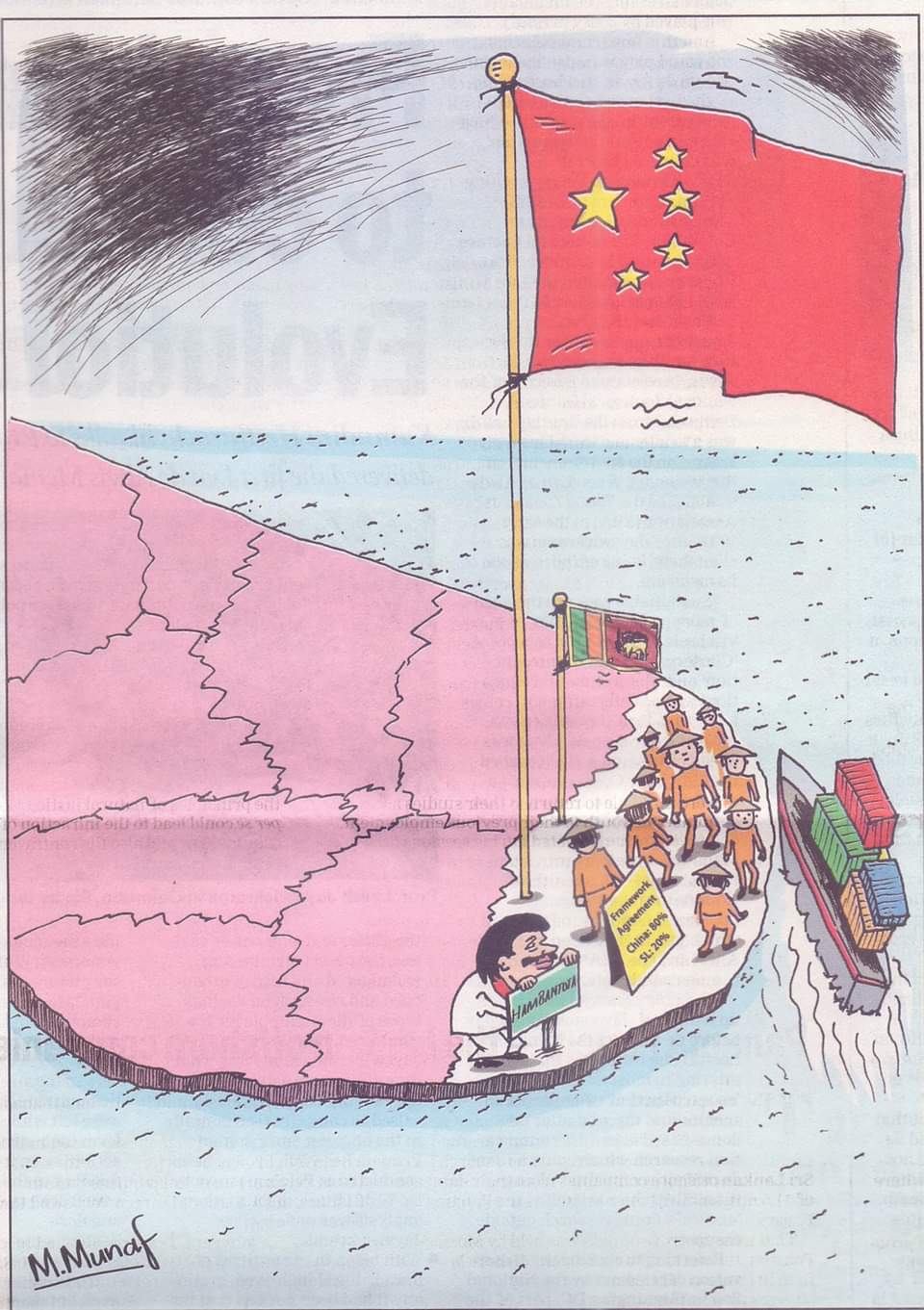

Analysts say the billions of dollars spent on Chinese-funded projects deepened Sri Lanka’s woes. Estimates are that the share of Chinese loans in Sri Lanka’s $40 billion debt range from 10% to 20%.

“China is known for working out arrangements that often turn out much costlier than just looking at the paper would tell you,” said Harsh Pant, vice president for studies and foreign policy at the Observer Research Foundation in New Delhi. “The inability of the Sri Lankan political class to understand the long-term consequences of the kind of short-term gains that they were making from China has allowed this to happen.”

Sri Lanka was one of the countries to sign onto China’s Belt and Road initiative under which Beijing extends loans to developing countries to build roads, airports, seaports and other infrastructure.

Sri Lanka’s debt to China could make it harder to push back against Beijing, according to analysts. In August, Sri Lankan authorities initially refused permission to a Chinese navy ship, Yuan Wang 5, to dock at the Chinese-built Hambantota port following objections by India and the United States, but later allowed it to come.

China has called the ship a scientific and research vessel, but security analysts said India was concerned because it was a surveillance ship packed with space and satellite-tracking electronics that can monitor rocket and missile launches.

The incident reinforced worries that the Chinese projects are linked to its strategic ambitions in the Indian Ocean. The Hambantota port was leased to China for 99 years in 2017 when Sri Lanka was unable to pay back the money borrowed to build it. That raised fears in India and Western countries that the port could be used by China’s navy to project power in the Indian Ocean, a vital seaway for global commerce.

“From my findings I found that these projects are more than a civil operation in Sri Lanka. There could be a military operation that they would introduce in the future such as from Hambantota,” according to Abeyagoonasekera.

China strongly rejects such concerns. At a foreign ministry briefing last month, Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian said that “China has never attached any political strings to its aid to Sri Lanka or sought any political interests from its investment and financing in that country.” Saying that Beijing empathizes with Sri Lanka’s difficulties, he said that “China has also been offering assistance to the economic and social development in Sri Lanka within its capacity.”

Sri Lanka is now hoping to hold early talks with China to restructure its debt, which is crucial to secure a $2.9 billion bailout from the International Monetary Fund.

Colombo reached a staff-level agreement with the IMF in September for getting the loan, but it is contingent on assurances from its creditors, including China, India and Japan, that the debts will be restructured.

VOA (Source)