In northern Jaffna ahead of the annual Tamil harvest festival of ‘Thai Pongal’, President Ranil Wickremesinghe promised the full implementation of the India-facilitated 13th Amendment as the way forward to restore ethnic peace in full. Coming as it did after his none-too-distant uttering that he was for ‘13-A minus police powers’, he has to clarify what he meant this time.

If Wickremesinghe is all for 13-A, why should he delay full implementation? After all, 13-A has been in the statute book for over 36 years, since 1987, when Parliament passed it. It was aimed at giving a constitutional accent to the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord earlier in the year, by President J R Jayewardene for Sri Lanka and Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi of India.

The Accord was an expression of the larger Indian neighbour to help usher in ethnic peace, hence prosperity, in the island-nation. After all, India was not a domestic stake-holder, but by signing the Accord, New Delhi was also sending a clear message not only to the SrI Lankan State but also to the Sri Lankan Tamil community, whose case it had taken up with Colombo in every which way.

It had become clear that neither the LTTE, claiming to be the ‘sole representative’ of the SLT community would sign what was otherwise an agreeable agreement, nor would it allow other militant and moderate Tamil groups to sign the document. Having shepherded the negotiations between the government and the LTTE from the start, neither the Indian State, nor Rajiv Gandhi as Prime Minister could allow the opportunity to slip by.

That’s if the Tamils were to get their due within a unified Sri Lanka sans separation as the LTTE was campaigning, through its three-pronged attacks, politically, militarily and through unending acts of terrorism. The LTTE targeted fellow-Tamil leaders at tangent with its leadership than any new ideology as much as the Sri Lankan State and symbols of the Sinhala-Buddhist majority like renowned Buddhist temples.

Diluting the spirit

Today, President Wickremesinghe seems convinced that 13-A is workable (but not functional). Successive governments since 1987 have diluted the spirit by side-stepping 13-A in key aspects of power-devolution by creating ‘national schools’ and ‘national hospitals’, which the Tamils naturally resented. The truth is that like 13-A with its universal applicability these national institutions that aimed at improved quality and services were set up also in non-Tamil areas.

If anything, more of these institutions cropped up outside the Tamil areas. It was because of the LTTE war that delayed development in the Tamil areas. It has remained so to the present, 15 years after the conclusion of the ethnic war.

If only a (unified) North-East Tamil Province was in existence, it could have argued for the diversion of federal funds that went into creating national schools and national hospitals to the provincial administrations, for them to build and operate them. They could have also ‘educated’ and ‘united’ the seven provincial administrations, elected under the 13-A in the Sinhala South, to take a unified stand in the matter.

Today, there is no knowing if the once-touted if the association of the provincial councils have met in recent years. With no elected administration in any of them, the association has become defunct. It is another instance of the federal administration arrogating to itself the powers vested in the provinces under the Constitution – dissolving them at whim all at once and not holding what should have been once-in-five-year periodic elections.

Specific restrictions

Any improvement to the 13-A, as sought by the divided Tamil polity, should include specific provisions specifying the powers of the federal centre to interfere with the administration of provincial councils, dissolve them and order fresh elections – but within a specific time-slot. If nothing else, at every such extension, like the monthly extension of emergency powers required, a parliamentary vote should be taken.

A majority/majoritarian government / leadership could do it without effort. Yet, the idea of a parliamentary vote by the month, or every quarter, could bring the issue back to the national platform, where TV debates and social media discourses could embarrass the polity and political administration enough to order early polls.

In specific cases, government leaderships that were delaying provincial council polls for fear of losing them may soon find that the unjustified delays themselves would be the top reason for their losing it, whenever held. President Wickremesinghe should get the credit or discredit for delaying PC polls almost indefinitely since his days as Prime Minister under the government of President Maithripala Sirisena, who was in power from 2015-2019.

Local economy

In Jaffna, Wickremesinghe told the local business leaders thus: “If we examine the provisions of the 13th Amendment, there is ample authority to establish a robust local economy. We pledge not to intervene in those affairs. I am encouraging you to take the initiative.”

As Wickremesinghe pointed out, the Western Province with capital Colombo at its politico-economic centre, is the sole region capable of substantial independent -spending, while others are financially dependent on it, he said. “This situation warrants reconsideration. By utilising the powers within the 13th Amendment, each province can chart its course to development. It’s time to put these powers into action,” he said.

When the Western Province is the only one that is economically viable, what does Wickremesinghe intend doing to mid-wife the other eight to achieve self-sustainability. Tamil political and social leaders, including those that trigger them from the confines of their more comforting Diaspora settings overseas, should give a deep thought to it all, if they want not to be left out – either as a people or province or political entities.

Innocent victims

The Tamil leadership missed the bus at least once earlier in the post-war period, they cannot afford to miss it again and again and bemoan later that they had committed a mistake again (‘meendum pizhai vittom’). That was when the TNA caused the government to walk out of well-advanced talks post-war, by aligning with the US and diverting national and global attention away from a political solution to war crimes. A decade later, the Tamils have neither.

Already, the post-war generation, including those who were then below ten and who had suffered the horrors of the horrendous war without being a part of it in any which way other than as innocent victims, has a life of its own to live. They are already living it.

The more the war moves away from them in calendar years, the greater this gap will be. In the same house, the grandparents would still be talking about SJV and Amirthalingam, the parents still sympathetic to the LTTE constantly evaluating and re-evaluating as to what (all) went wrong, Gen X, Y and Z, amusedly looking at one another as to what their (fossilised?) family elders were talking about.

The present-day Tamil political and social leaderships have already lost credibility even among their own generation. The newer generation(s) has/have utter contempt for them, if not worse. Both sections demonstrated their distrust for their otherwise divided political leadership even when they gave a joint call late last year, first for a human-chain and later for a day-long ‘hartal’ or ‘shut-down’ on the ‘Judge Saravanarajah’ issue.

Both the human-chain and substitute hartal failed miserably, sending out a clear message from the Tamil people to their own leaderships. The latter’s connectivity to issues real and/or imaginary were exposed when credible doubts were raised about the truthfulness of Saravanarajah’s resignation and exit from the country. It turned out that the hon’ble judge might have faked the issues, fully or partially, to create sympathy for himself and the larger Tamil cause, for exiting the job legally and then leaving the country – which he seemed to have organised early on.

Selfish but…

Even if Wickremesinghe were to look at his current promise on 13-A from a selfish stand-point, he only needs to take real initiatives whose effects can be felt on the ground, for him to win over a substantial section of Tamil votes. With that and similar initiatives viz the Muslims and Upcountry Tamils, he may have a majority of the ‘minority votes’ in his pocket.

As calculations have shown, nearly 25 per cent of the 42-per cent of the votes that went to the losing Sajith Premadasa, then in Ranil-led UNP, came from the minorities. If Ranil could woo them back through substantive measures that those voters can touch and feel in time for the presidential poll, he may have to work only for another 25-30 per cent votes from the Sinhala South to make the grade in the presidential polls later this year – and retain the presidency.

There is a catch. The post-war regime of Mahinda Rajapaksa having made major progress in talks with the TNA, including freedom for the Tamil province to seek and obtain direct foreign funding, loans and investments, Ranil only needs to put that into practice. Given that every nook and corner of the country can do with those extra dollars, the freedom should be made operational and extended to every Province.

But for all this, to begin with, the President has to set the date for nation-wide PC polls, here and now, even if it is later in the year, after the presidential polls and before or after the parliamentary elections, which again he has promised for the year. He cannot continue to build castles in the air and expect the people to believe that they are living in them already.

That will still leave behind two major issues. One, re-merger of the North and the East, as the Tamil polity wants. That may have to wait until after the presidential, parliamentary and even provincial council elections. Possibly, the younger generation may not be too keen on them, as they may not share the emotional attachment that SJV instilled after he had to shift base from the North to the East when he lost the 1952 parliamentary polls from his native Kankesanthurai constituency in the North.

Barking up the wrong tree

The second issue is about police powers for the provinces. It has made some progress when the government was talking to the TNA, post-war. In his stalemated rounds of talks with the Tamil parties and with all the rest, Wickremesinghe indicated that he was ready to move on with 13-A minus police powers.

For the Tamils, it would be a letdown. For the Tamil polity it would have been worse as the entire LTTE war in a way was for police powers and re-merger. Yet, if Wickremesinghe was serious, even about 13-A minus the police powers, he should have begun it somewhere. By implication, it needed only executive order(s) to put 13-A into practice. He has not done it either.

Yet, for all that he has been promising the Tamil people and polity, including his address to the Jaffna business community, Ranil or Wickremesinghe or Ranil Wickremesinghe is barking up the wrong tree. He should have begun with the southern provinces and southern polity, to tell them how 13-A had provisions that would make them all economically strong, self-reliant and independent, even if over the years and decades.

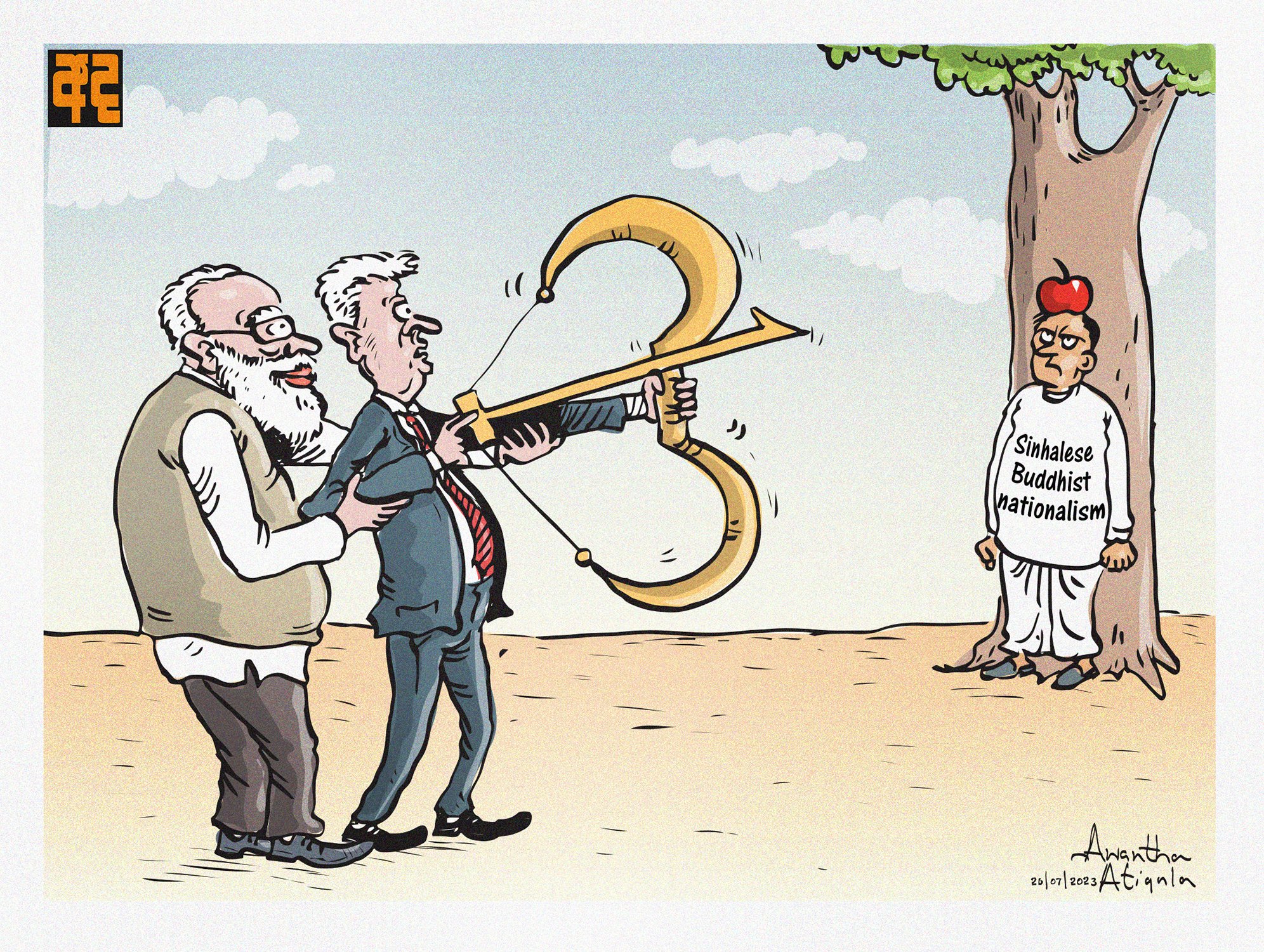

That is, if they had begun in 1987, they all would have become prosperous by now, and would have helped the country to become more prosperous than what alone a stand-alone Western Province has been supposedly shouldering and failing, successively, since Independence, and before. That being the case, is economic prosperity of the nation that the Buddhist clergy is denying the people, that too at this critical hour, in the name of wanting a ‘unitary State’ structure without understanding, hence appreciating, the economic nuances of the 21st century.

Maybe in public, maybe not, but the government, whoever is in power, has to engage the Buddhist clergy, including the prelates, in an economic discourse, as a part of the burgeoning possibilities and problems of a resilient nation that the present generation has to leave behind for the future, near and distant. Well, it can begin now. An element of defiance, when put into practice, can also show the benefits of 13-A for the people from across the country to touch, feel and benefit from – and which in turn can silent, if not stupefy, all sections that are opposed to it, under wrong notions and influences.

It has to begin there, begin there early, here and now.

(The writer is a Policy Analyst & Political Commentator, based in Chennai, India. Email: sathiyam54@nsathiyamoorthy.com)