Reams can be written on the tragedy called Sri Lanka, and wagonloads of midnight oil can be burnt in debating the causes and remedies for this human disaster that consumed three generations and is threatening the health of the gen-next. India cannot ignore this latest Lankan tsunami of shortages, especially with the stalking Chinese dragon eyeing to gobble up the island and open a new battlefront barely 30 minutes by speedboat across the Palk Strait down south.

Sri Lanka, the lovely little pearl of the Indian Ocean, should not be in such deep distress, not so frequently. The Eelam war ended in May 2009 after consuming close to 2.5 lakh lives and just when the world expected the tear-shaped island to start smiling at spiking inflows into its treasury through a revival of tourism, tea exports and remittances of its citizens working abroad, yet another crushing load of woes has sunk it deeper. Redemption seems pretty tough unless a series of miracles happen from multiple magic wands, even as the rulers in Colombo and their detractors remain locked up in their selfish agendas.

With the decimation of the Tamil Tigers and their dreaded leader Velupillai Prabhakaran, President Mahinda Rajapaksa was hailed by the Sinhala majority (constituting about 75 per cent of the 22 million population) as the saviour of the country, a reincarnation of Emperor Dutugemunu, the legendary Sinhala king who had vanquished a Tamil monarch and unified much of the country under his rule over 2000 years ago. He was crowned by his masses as the Lion in the Sri Lankan flag (it has a roaring lion holding a raised sword in one hand).

Read | Gota’s gotta go, Lankans say, Destination Uganda?

Mahinda’s brother Gotabaya, the powerful defence secretary who had steered the war victory along with the military commander, General Sarath Fonseka, was his poster-mate when the presidential election was held eight months later, in January 2010. Mahinda won with a huge margin against his rival Fonseka, who was then put up as the combined opposition candidate in the hope he would be able to steal some of that war glory.

Riding regally upon the yuan-spitting Chinese dragon, ‘Emperor’ Mahinda has had a free run of Sri Lanka but for a brief topple in January 2015 when he lost the presidential election to his little-known cabinet colleague Maithripala Sirisena. He blamed India’s RAW for his defeat.

The Chinese quickly retrieved the throne for Mahinda after ‘neutralising’ Maithri with their time-tested therapy of bribes and bubbly perks. By the end of 2019, the Rajapaksa family was back in control, while pro-Delhi/pro-West Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe of the rival UNP lost his seat in what was then seen as the first big victory for China over India in the tussle for control of the island.

With no challenger visible anywhere on the political horizon, Mahinda could have ruled the country for life if only he had not chosen to drown it in high corruption. Had he used his post-war popularity to push for constitutional reforms that replaced Sinhala supremacy with multiracial inclusivity, he would have gone down in history as one of the greatest statesmen in the world.

Instead, Mahinda, along with his Rajapaksa clan, chose to waste the opportunity that destiny presented him with. As the country thus seemed to be heading for disaster, the present crisis was hastened by a series of stupid revenue-depleting decisions—such as cutting taxes during the Covid hit, shifting the island’s agriculture to the less-yielding organic mode and using up huge chunks of foreign borrowings for servicing external debt and to create unproductive fancy structures.

A steep drop in foreign exchange reserves needed to import the essentials such as food, fuel and medicines led to unprecedented shortages of essentials. The expected happened when the finance ministry on April 12 admitted there was no option but to default on the $51 billion external debt, awaiting a bailout from the International Monetary Fund.

When the hungry-angry Sinhala people marched to President Gotabhaya’s house demanding he quit office, Gotabhaya saw an external hand—read India—in the rebellion and vowed not to quit. Hoping to distract the public anger, Prime Minister Mahinda got his entire 26-member cabinet to resign late-night April 4, but he stayed put in power.

Mahinda brought in Ali Sabry as his finance minister in a move seen by many as placating the oil-rich Gulf region. Sabry resigned within 24 hours but announced later he would rather stay since nobody came forward to accept the responsibility.

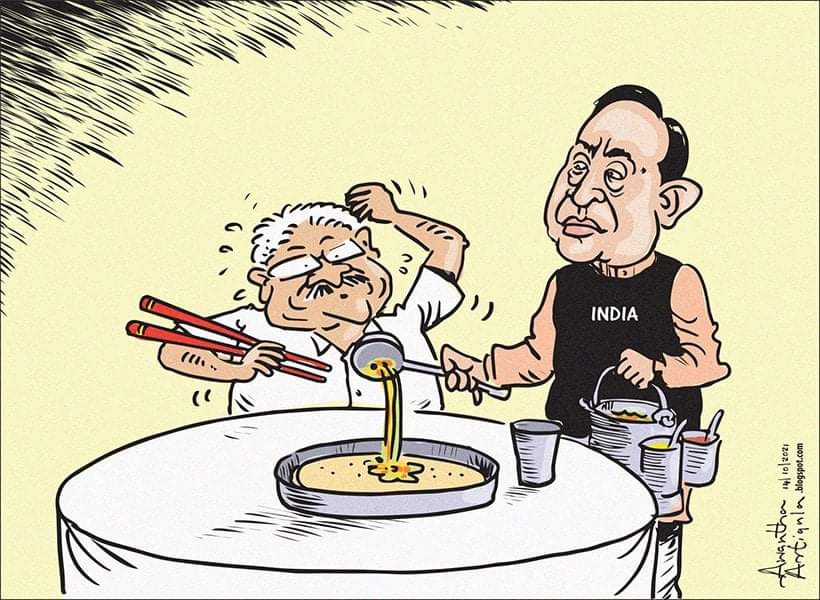

While China gleefully fanned the greed and arrogance of the Lankan First Family, getting in return one major project after another and gradually inching towards taking control of the island to strengthen its ‘String of Pearls’, India seemed to have all but lost the game. Delhi woke up to the threat of a new battlefront evolving down south only when the Chinese Ambassador Qi Zhenhong undertook a provocative trip to Jaffna (December 2021) and declared, “This is just the beginning”.

A series of quick remedial measures undertaken by the External Affairs Ministry, backed by a determined prime minister keen on India keeping its regional interests preserved and the loosening of purse strings by the Finance Ministry, plus the QUAD support, led to India stepping up its role to help Sri Lanka from its crisis. In this process, Delhi also managed to get Colombo to sign up six agreements during External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar’s visit there in March.

Three of them are of great strategic significance—wresting from China the project to build hybrid power projects in three Palk Strait islands close to south Tamil Nadu; creating a maritime rescue coordination centre that would mean access to the Sri Lankan air and sea space for Indian air-sea craft; and, helping in the maintenance and upgrade of fisheries harbours in the island. Needless to say, the last-mentioned project could bring almost the entire island coastline under India’s scrutiny if not controlled.

Of course, all these ambitious deals could get derailed by some succeeding regime in this slippery political mosaic unless India maintains its firm grip over the southern neighbour by keeping its lifeline going for the Sri Lankans from its own resources and through ‘safe’ collaborations with international financial institutions, such as the IMF, while also creating a monitoring mechanism to ensure that all the global aid coming into the island is properly utilised.

In this process, two challenges need to be overcome by some deft Jaishankarian diplomacy – winning the confidence of the majority Sinhala population that always had deep suspicion if not allergy towards India while regaining the support of the Tamils that was lost when the Eelam war collapsed, and they accused Delhi of collaboration in the massacre.

The second big challenge would be to get democracy back on its feet in Sri Lanka and help bring in a government that would be honestly friendly to India’s geopolitical interests, which means keeping a safe distance from the Dragon. This is the first time since their ascendancy that the Rajapaksas are facing this kind of Sinhala street anger, and Delhi must help in politically channelising this into positive energy for the good of the region.

External Affairs Minister Jaishankar seems to be on the right track and must work harder in bringing in the Tamil leadership to fall in line as well; right now, most of these Eelathalaivars with expiry tags stuck to their punctured lapels are squabbling over the leadership of the Tamil National Alliance (TNA). This is what I had meant when I spoke of miracles happening off multiple magic wands.

(R Bhagwan Singh is a senior journalist based out of Chennai, writing on Sri Lanka since the 1980s)

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author’s own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.