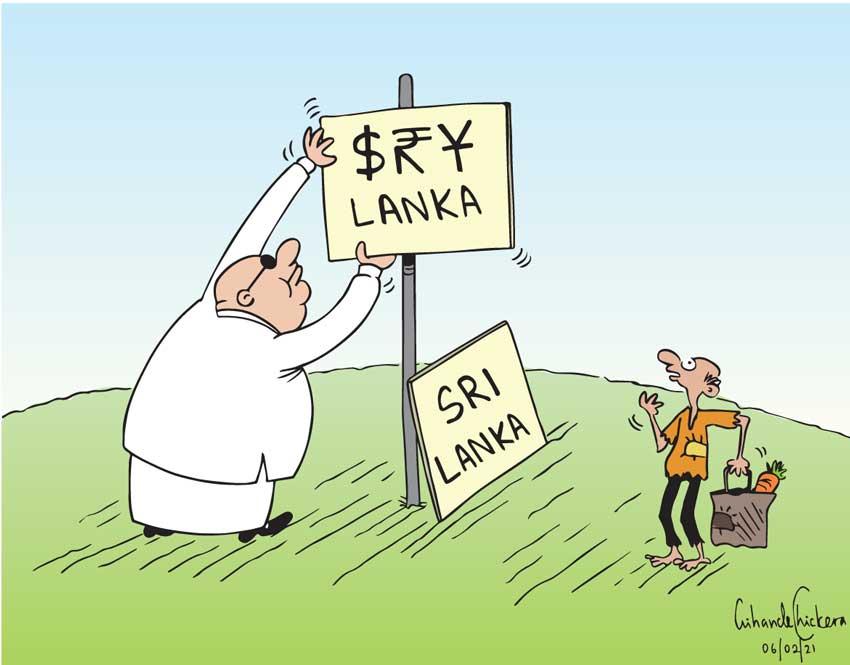

Faced with low foreign-exchange reserves and looming debt repayments, Sri Lanka is borrowing from the contrarian playbook Malaysia used during the days of the Asian crisis in 1998.

The island nation has imposed some form of capital controls and curbs on imports in signs that it’s turning inward, partly to end reliance on the International Monetary Fund before $ 3.7 billion of foreign debt matures this year.

The measures, such as repatriation of export earnings within 180 days from shipment, conversion of some export proceeds into rupees and getting commercial lenders to surrender a portion of their forex receipts to the Central Bank, are aimed at stopping the reserves from bleeding in the absence of loans from the IMF and revenue from tourism amid the pandemic.

That would help the country to rely on its own resources instead of foreign borrowing, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka said in a statement on 23 February. The steps will strengthen Sri Lanka’s credit profile, enhance exchange rate stability, and improve the resilience of the economy, it said.

What these measures also do are to help fend off interference from the IMF, whose aid comes with strict conditions – one of the reasons that prompted Malaysia’s then premier Mahathir Mohamad to shun aid from the lender despite descending into a recession following the Asian currency crisis. The IMF last year prematurely ended a loan program to Sri Lanka after disbursing $ 1.3 billion of an agreed $ 1.5 billion facility, leaving the nation scouting for ways to tide over the pandemic-induced downturn.

Sri Lanka has to repay $3.7 billion to holders of external debt this year, according to Central Bank Governor Weligamage Don Lakshman. The South Asian nation is expecting $ 32 billion from exports of goods and services, remittances and financial inflows, while the outflows are estimated at $ 27.6 billion, leaving a $ 4.4 billion surplus to service the debt, State Minister for Money and Capital Markets Ajith Nivard Cabraal said separately.

“The main thrust is to reduce the government’s reliance on foreign borrowings,” Citigroup Inc. analyst Johanna Chua wrote in a report on 25 February. “The odds of the July 2021 bond being repaid seem rather high given the willingness to pay,” she said.

Sri Lanka’s dollar bonds due in March 2030 are indicated at 59 cents on the dollar, according to prices compiled by Bloomberg. That compares with a high of 84 cents on the dollar in September 2020 before major rating firms downgraded the nation deeper into junk.

Although forex reserves this January fell to $ 4.8 billion from $ 8.9 billion about two years ago, they are enough to cover a little over three months of imports. The island nation is separately negotiating swaps and loans from countries including China and India to build its reserves buffer.

“It is the Government policy to work as much as possible to resolve our foreign exchange policies on a self-reliant basis and to hold discussions with institutions and organisations and countries which are willing to assist on a relatively non-interventionist basis,” Lakshman said in January.

That rules out the IMF, whose prescriptions for assistance included fiscal consolidation and removing caps on borrowing costs. The Government, in its latest budget, proposed increasing spending this year to support the economy, while the Central Bank, for its part, kept interest rates at a record low.

Sri Lanka is close to securing a $ 1.5 billion swap with China’s Central Bank, Cabraal said last month. Besides, discussions are on for loans worth $ 700 million with China Development Bank, Treasury Secretary S.R. Attygalle said.

Sri Lanka is following a market-oriented economy with State guidance, involving some controls and restrictions, according to Governor Lakshman.

“Such a framework would not be successful under an IMF program,” he said.

Source: Bloomberg