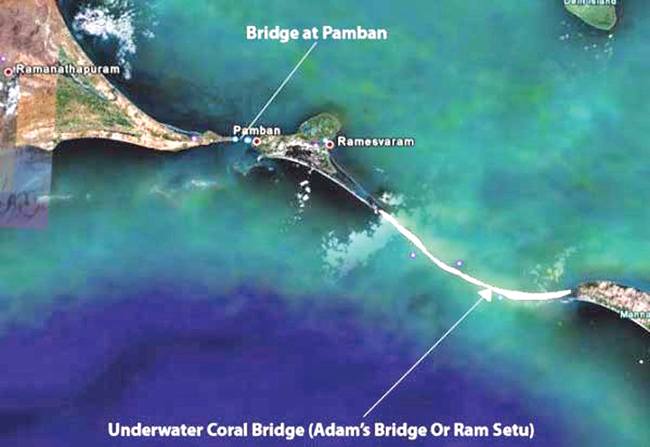

On January 12, the Tamil Nadu State Assembly unanimously adopted a government resolution urging New Delhi to immediately implement the long-pending “Sethusamudram project” which envisages a canal cut through the Gulf of Mannar and the Palk Strait to facilitate ship movement between the East and West coasts of India by the shortest route.

The proposal to cut a canal in the shallow sea dividing India and Sri Lanka to save on coast-to-coast journey time and promote the development of South Tamil Nadu, has been objected to in India on navigational, environmental and economic grounds. Since the project will have an impact on Sri Lanka too, objections have been raised in the island also.

Although Sri Lanka has an environmental impact assessment procedure for coastal conservation, the Sethusamudram project was not brought under its jurisdiction because it was to be within India’s territorial waters. But despite this, it is felt in Sri Lanka, that its environmental concerns have to be addressed given the proximity of the proposed canal to Sri Lanka. However, the Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) of the project carried out by India is said to have alluded to Sri Lanka only in passing.

Calls by Sri Lankan environmental groups for a joint Indo-Lankan Environmental and a Social Impacts Assessment fell on deaf ears in India, claim S. C. Withana and C. V. Liyanawatte of the Sir John Kotelawala Defence University in Sri Lanka, in their 2016 paper entitled: “Sethusamudram Ship Canal Project adverse to Sri Lanka?” Legal and Environmental Impact on Sri Lanka.”

They say that in 2005, Sri Lanka had sought the establishment of a standing joint mechanism for exchange of information on the project. It wanted to set up a common database on hydrodynamic modelling, environmental measures and the impact on fish resources, fisheries-dependent communities and also on measures to cope with navigational emergencies. They also contend that the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) had been violated.

Like the Indian environmental activists, Withana and Liyanawatte point out that the environmental impact study carried out by the National Environmental Engineering Research Institute (NEERI) of India in 1988 and the technical feasibility report carried out for the Tuticorin Port Trust (TPT) had failed to pay attention to the latest studies carried out by specialist groups on sedimentation dynamics in the Palk Bay and ignored major risks inherent in that cyclone-prone area.

Since the project is to be implemented in an ecologically sensitive area, the researchers quote Article 15 of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development of 1992 which says: “In order to protect the environment, the precautionary approach shall be widely applied by States according to their capabilities. Where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation.”

The executive summary of the EIA on the canal project itself says that the 83 km deep water channel is to be built in a biologically rich and highly productive sea area. There are over 3600 species of plants and animals, including 117 species of corals and 17 species of mangroves. Further, the EIA report states that this area is home to rare species such as sea turtle, whales, dolphins and sea cows. The sea cow is a rare and endangered species migrating with the change of seasons.

“Dredging the canal could stir up the dust and toxins that lie beneath the sea bed, affecting marine life,” the Lankan researchers say. The canal will damage coral reefs too. Further, by damaging the ecology of the zone, there could be changes in temperature, salinity, turbidity and flow of nutrients, leading to high tides and more energetic waves and hence coastal erosion. The pattern of sea breeze and rainfall pattern will be altered they say echoing Indian environmentalists. R.K. Pachauri, who was Chairperson of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), had said that the project would not be “economically and ecologically viable.”

Resort to UNCLOS

Withana and Liyanawatte suggest that Sri Lanka could use the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) for getting redress.

Article 235 (1) of UNCLOS says that: “States are responsible for the fulfillment of their international obligations concerning the protection and preservation of the marine environment.” Art. 194(2) recognizes that: “States shall take all measures necessary to ensure that activities under their jurisdiction or control are so conducted as not to cause damage by pollution to other States and their environment and that pollution arising from incidents or activities under their jurisdiction or control does not spread beyond the areas where they exercise sovereign rights in accordance with this Convention.”

Article 235 (3) mentions that: “With the objective of assuring prompt and adequate compensation in respect of all damage caused by pollution of the marine environment, States shall cooperate in the implementation of existing international law and the further development of international law relating to responsibility and liability for the assessment of and compensation for damage and the settlement of related dispute.”

The Sri Lankan researchers point out that Section 2 of part XV of UNCLOS has general provisions dealing with the settlement of disputes by negotiations. Article 283 says that “when a dispute arises between state parties concerning the interpretation and application of the convention, the parties to the dispute shall proceed expeditiously to an exchange of views regarding its settlement by negotiations or other peaceful means”.

Withana and Liyanawatte say that Sri Lanka and India could negotiate for a dispute settlement mechanism. Sri Lanka could point out that India had not exchanged views regarding the project with Sri Lanka.

“If India is looking at continuing the project notwithstanding the objections of Sri Lanka, Sri Lanka can move on to the compulsory procedures entailing binding decisions according to Article 287. Sri Lanka can move on to a settlement of disputes by compulsory procedure through the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS),” they suggest. In 2003 Malaysia had complained against Singapore over ‘Land Reclamation’ and got a ruling in its favor.

Be that as it may, the implementation of the Sethusamudram Ship Canal Project (SSCP) is not at all certain although the Tamil Nadu State Assembly has passed a resolution on it unanimously, with even the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) supporting it.

Firstly, the environment-protection lobby is strongly against it. Shipping experts have maintained that constant dredging will be needed and the time saved by using the canal rather than taking the circuitous route around Sri Lanka will be negligible as the speed of ships will have to be curtailed drastically when traversing the canal. Experts have even said that the huge expenditure to be incurred in cutting the canal and maintaining it cannot be justified.

Lastly, Dr. Subramanian Swamy, a vocal and activist BJP Member of Parliament, had gone to the Supreme Court against the project, citing religious objections. His plea was that the canal will cut the “Rama Sethu”, which is a string of limestone shoals Hindus believe constituted the bridge Hanuman had built to enable Rama and his army to cross over to Lanka to fight Ravana according to the epic Ramayana. The shoals are also said to be of importance in Abrahamic religions for they are believed to be Adam’s footprints. Hence the English name ‘Adam’s Bridge’ for Rama Sethu.

The Supreme Court had stayed the project in 2007 due to Swamy’s petition. In 2018, the Indian government told the court that it intends to explore an alternative alignment so that no damage is done to the Rama Sethu. That alternative has not been worked out yet.