The well-earned publicity that the ‘Integrated Country Strategy’ for Sri Lankan missions in India has received in the Indian media is welcome for more reasons than one. In particular, it deserves to be praised for acknowledging the ‘trust deficit’ that has re-emerged in the bilateral relations over the past year—after a relatively smooth sail in the five years before it.

With the acknowledgement also comes suggestions for setting right many, if not all the causes for the ‘trust deficit’. The latter has more to do with the contemporary political and economic realities, as different from the centuries-old cultural underpinning, from which both nations have unfortunately moved away over the past decades.

When cleared by the government of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, the document could be the guiding, if not the governing, principle for Sri Lankan missions in India, after the former Minister Milinda Moragoda takes over as the High Commissioner in Delhi later this month. Moragoda having authored the strategy paper along with his mission counterparts in Delhi, Chennai and Mumbai, the authors are also the implementers—and thus, know the dos and don’ts that lie ahead for them.

Age-old links: Naturally, the strategy paper refers to Buddhist links between the two nations, which actually dates back prior to the commonly-known era of Emperor Ashoka. In contemporary terms, the paper has proposed for Sri Lanka to send a stone from ‘Sita Eliya temple’ in Nuwara Eliya district, linked to the Indian epic, ‘Ramayan’, for the Ram temple construction at Ayodhya in north India.

Despite possible political fall-outs in India, especially in the future, the suggestion should be welcomed. It may slow down, if not set at naught, the recent efforts in Sri Lanka to establish Ravan, the antagonist in Ramayan, as a Sri Lankan sovereign independent of the Indian epic and also the earliest aviator in the world.

TRANSACTIONAL APPROACH

It is, however, in the contemporary context that the paper’s acknowledgement of trust-deficit between the two South Asian/Indian Ocean neighbours assumes immediate relevance and significance. As the report candidly acknowledges, “In recent years, the Indo-Sri Lanka bilateral relationship has been increasingly dominated by a transactional approach.”

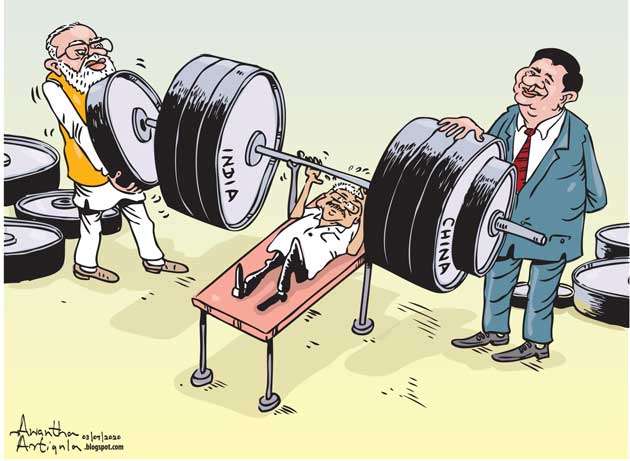

There is truth in the assessment that the historic relations between the two nations have long since given place to self-centric claims, expectations and denials by both. Neither does India possess the elder brother/sister attitude any more, nor is Sri Lanka willing to stop playing the recently-innovated ‘China card’ viz its northern neighbour.

The “Team Milinda” paper, as it could be called, says that the ‘transactional approach’ is a ‘consequence of the changes in the geo-political equilibrium in the region that have resulted in a growing trust-deficit’. In diplomatic terms, this should be construed as a reference to China emerging as the bugbear in Sri Lanka’s India relations in recent years—but without naming the extra-regional power.

In real terms, China in this case is pitted more against the US than India, just as the latter pitted itself against the erstwhile Soviet Union in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) during the Cold War era. But the end result is that the Chinese presence in and domination of the Sri Lanka scene, especially in economic and political fields—and not necessarily in that order—has nullified all efforts at improved ties between Colombo and New Delhi in the post-war era.

INVESTORS UNSURE

It suffices to point out that in the aftermath of the aborted trilateral deal on the East Container Terminal (ECT), also involving Japan, after President Gotabaya took over, Indian investors, big and small, have become unsure about putting in big money in the island-neighbour. True or not, they have come to believe that a twitch of the lips in distant Beijing could push Colombo to throw them out halfway through.

The one exception is the West Container Terminal (WCT) construction concession offered to the India-based Adani group, as if in lieu of the cancelled ECT pact. The strategy paper suggests that the WCT proposal should be cleared without delay. Other Indian investors would be closely watching developments on this front before deciding to put their money in Sri Lanka. In effect, this means that Colombo cannot hope to get all, or even much of the US $256-billion Indian FDI by 2022, as the Milinda paper recalls.

INCREASING PROTECTIONISM

Yet, there is truth in the strategy paper’s claims on wanting to realise US $675-million Sri Lankan exports to India, again by 2022. As the study points out, export prospects at present suffer from “increasing protectionism (in India), limited market access, a challenging and unpredictable regulatory environment as well as the ‘Make in India’ initiative, which prioritises local business and sourcing of local raw materials and products over imports”.

True, Prime Minister Narendra Modi revived the Nehruvian ‘self-reliance’ goal in the name of ‘Make in India’ after coming to power in 2014. But no specifics have been made available for India to exempt raw material imports from Sri Lanka, as indicated. For close to two decades now, Sri Lanka has deliberately missed all opportunities to discuss Indian protectionism and non-tariff barriers with the sincerity and seriousness that they deserve as a part of larger trade negotiations, especially after the bilateral Free Trade Agreement (FTA) in 1998 had proved its worth and usefulness for both.

Long before Modi came to power, bilateral trade had suffered and a trust-deficit made an appearance, instead, after the two nations initialled the forgotten Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on a Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) at Colombo in 2008. Sri Lanka pulled back from signing the formal pact in the aftermath of a later-day anti-ECT kind of protest. The alternative ETCA negotiations for an ‘Economic and Technology Cooperation Agreement’, proposed by the successor Wickremesinghe regime, too fell by the wayside, again, as designed by Colombo.

TROUBLE SPOTS

In an altruistic fashion, Team Milinda’s strategy paper has focussed on Sri Lankan missions in India improving relations with Indian states, directly, wherever possible. It will bear fruit especially in terms of investments and large-scale trade for the Sri Lankan Consul-General in Mumbai to take up.

The real and unmentioned crux, however, lies in southern Chennai, which used to harbour strong views on the Sri Lankan ethnic issue and also the fishers’ dispute. The former is still an emotive matter, and the latter a life-and-livelihood concern in Tamil Nadu.

The strategy paper does not mention the ‘ethnic issue’, on which not only the government but people of Tamil Nadu are also concerned about. Then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi had signed the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord on the ethnic issue along with Sri Lankan President J.R. Jayawardene in July 1987. Hence, the Government of India continues to have similar and at times stronger concern about the Colombo dispensation having to meet the ‘legitimate aspirations’ of the island’s Tamil population—which has not happened, as yet.

As for the fishers’ dispute, successive political dispensations in New Delhi have reaffirmed its commitment to the 1974-76 accords on International Maritime Boundary Line (IMBL), thus conceding Katchchativu islet in Sri Lankan territory. On the larger issue of Sri Lankan Tamil fishers from the North especially continuing to oppose destructive trawlers from southern Tamil Nadu in particular competing with them in the waters that New Delhi has acknowledged as theirs, the issue remains to be resolved completely.

The ‘Milinda Paper’ makes great sense in wanting the affected fisher communities in the two countries to sort it out through negotiations. The talks that commenced as a private initiative obtained governmental blessings from both sides, but got stuck in the ocean waters at Chennai, in the first half of the last decade.

However, the Jayalalithaa-led AIADMK government in the state still took up the long-pending Centre’s proposal for equipping and training Rameswaram fishers, caught in the middle, in deep-sea fishing instead. The process is slow, and has also suffered owing to the rightful prioritisation of COVID pandemic management in the state.

In Sri Lanka, the Colombo government alone has all powers to negotiate on the fishers’ behalf, or facilitate such negotiations between fishing communities in the two countries. In India too, communication with foreign governments flow through New Delhi. It will, thus, be effective for the Sri Lankan government, the High Commission in Delhi, and the Deputy High Commission (DHC) in Chennai, amongst others, to continue communicating with the Tamil Nadu government and the state’s fishers through New Delhi—rather than directly.

Though unintended, Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M.K. Stalin seemed to remind Sri Lankan officialdom of the continuing Indian protocol in such matters, despite the political differences between Chennai and Delhi. Stalin wrote (only) to External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar—and not formally to any Sri Lankan authorities—on reports of Sri Lanka Navy (SLN) opening fire mid-sea, injuring a Tamil Nadu fisher, Kalaiselvan, in the head.

Yet, the Sri Lankan Deputy High Commission in Chennai could continue work with home office whenever Indian fishers are inconvenienced after Sri Lankan Navy (SLN) arrests them mid-sea, along with their boats. The free-wheeling facilitation by the DHC and early release of the Tamil Nadu fishers in the war years definitely created a feel-good factor in the state. In turn, it got reflected to some extent when the state’s fishers began negotiations with their brethren from across the Palk Strait—until personality-centric domestic politics derailed the process at the most recent round in Chennai, 2014.

This article was first published on ORF.

DISCLAIMER:The author is Distinguished Fellow and Head of ORF’s Chennai Initiative