Sri Lanka’s central bank credit (printed money) was a negative 8.7 billion rupees in September 2022 and private sector was also de-leveraging for the fourth straight month, official data shows.

Net Central Bank credit contracted 8.7 billion rupees to 3,302 billion rupees in September, down from 47.2 billion a month earlier.

Credit to government from the banking system was 53.3 billion rupees down from 163.7 billion rupees a month earlier.

Sri Lanka’s central bank has purchased some government securities from auctions outright in recent weeks but with high rates and private sector de-leveraging the money is not moving into the broader economy.

Private credit contracted by 37.3 billion rupees to 7,576.9 billion rupees in September, the fourth straight month of de-leveraging. Private credit contracte 58 billion rupees a month earlier. In June and July private credit contracted 40 billion rupees.

As a result money injected outright into the banking system, usually triggers a fall in overnight injections and not new credit which hit the balance of payments as import demand.

Related

Sri Lanka key current inflows exceed imports for fourth month in Sept

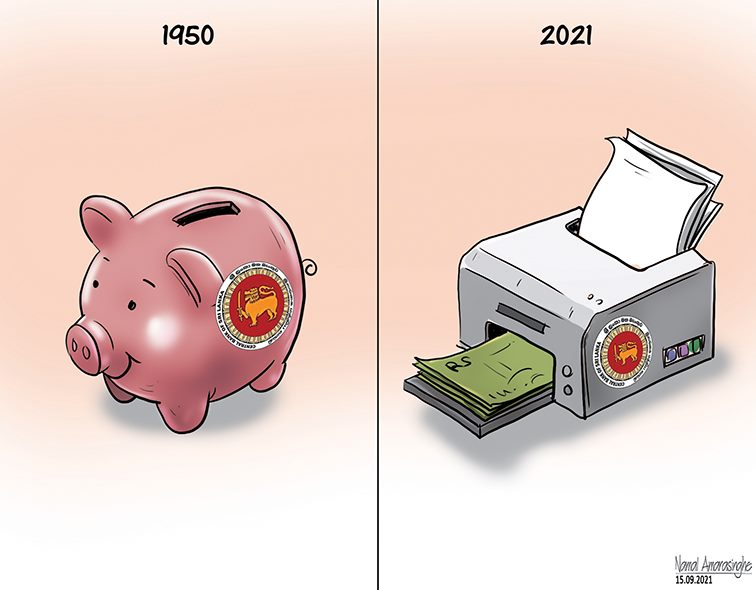

Sri Lanka’s central bank allowed market interest rates to move up with credit demand from around April 2022 to help the worst currency crisis created in the history of agency which was set up in 1950 in the style of a Latin America style intermediate regime with extensive sterilization powers in both directions.

A sterilizing central bank will usually print money to keep interest rates down, purchase maturing Treasury bills from past deficits injecting capital, and blame the budget deficit for its policy rate.

It will also buy Treasury securities from banks after intervening to maintain the peg, injecting what 19 century classical economists called ‘fictitious capital’ into the banking system to extend a credit cycle, build up imbalances and worsen a currency crisis by boosting bank credit without deposits.

Up to June the central bank also got Asian Clearing Union dollars from India to intervene and print money.

Latin America style central banks were set up especially to extend a credit cycle and resist a slowdown from the tightening of the anchor currency (the US Fed or the Gold area generally) by post 1931 macro-economists, creating unusually intense balance of payments crises. Such tightening is automatic in hard pegs.

A central bank is the only agency which can create high inflation or balance of payments deficits by suppressing rates through its policy rate and it is also the agency which can end them.

Sri Lanka in April allowed rates to go up to reduce credit, hiked taxes to reduce credit to government and also hiked utility rates to reduce credit to state enterprises.

State enterprise credit grew 3.2 billion rupees in September after falling 54 billion rupees in August.

Sri Lanka got into serial currency crises from 2015 by injecting liquidity into the banking system in the course of operating a ‘data driven’ flexible inflation targeting regime, a type of soft-peg with unusually aggressive open market operations to target an output gap (stimulus).

The regime has an inflation target as high as 6.0 percent, about twice the rate of other central bank allowing interest rates to be mi-targeted for a longer period. Policy errors are then compensated by currency collapses called a ‘flexible exchange rate’.