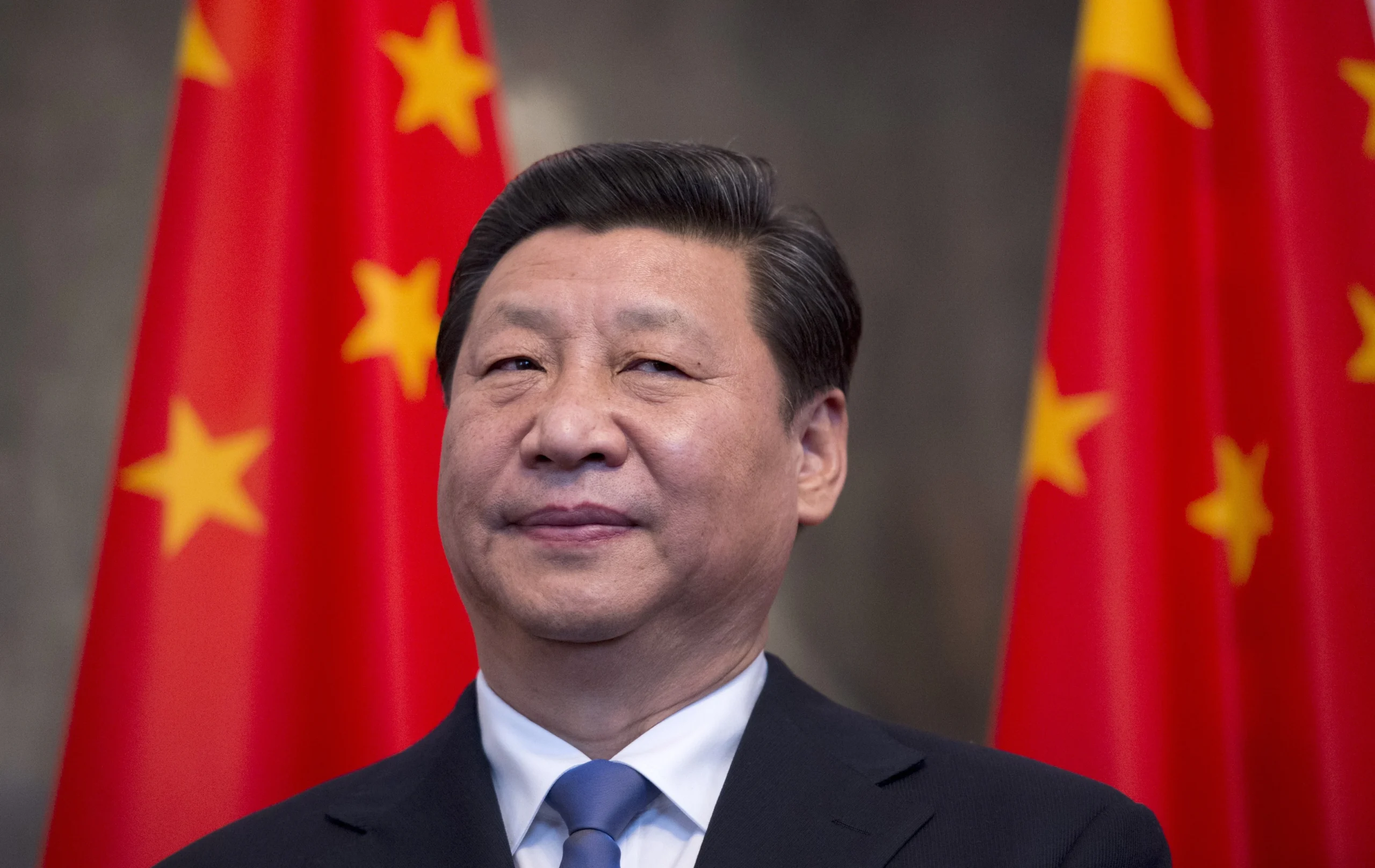

The 20th Communist Party Congress of China may put a hold on the Chinese restructuring talks with Sri Lanka to secure the $2.9 billion facility to revive the ailing economy.

The deadline was set for December, but it may be extended to January, according to the Central Bank of Sri Lanka. China is the main bilateral debtor, and the party congress may hinder December talks aimed at restructuring.

The next meeting of the IMF executive board is scheduled for March 23.

Hence, Sri Lanka will probably miss the December deadline for securing an IMF loan as its main bilateral debtor, China, was involved in the 20th Party Congress and had little time to hold debt restructuring talks with Sri Lanka. The next meeting of the IMF executive board is in March 2023.

Meanwhile, NIKKEI Asia reported in its latest dispatch that dollar-strapped Sri Lanka is hoping for a still-elusive $2.9 billion IMF bailout before beginning to rebuild usable foreign reserves, according to the head of the country’s central bank in a recent exclusive interview.

“Once the IMF starts disbursing their commitments following the IMF board’s approval, it will be the point at which we will start building our foreign reserves,” Gov. Nandalal Weerasinghe said.

The bankrupt South Asian nation reached a staff-level bailout agreement with the IMF in early September, subject to board approval. But Sri Lankans will soon be welcoming a new year amid continued economic hardship. For now, limited imports are being paid for with export earnings, remittances from migrant workers, and a trickle from the tourism sector as the authorities cling to paltry remaining funds.

Usable coffers slumped to historic lows of $20 million by April and have now inched up to $300 million. Officially, reserves hover at $1.7 billion, but this includes a $1.4 billion swap from the People’s Bank of China that cannot be tapped because of restrictive conditions. For example, Sri Lanka would have to save up its reserves to finance three months of imports, an estimated $5.1 billion, before China’s central bank approves access.

The two-step approach to restoring the reserves is part of the recovery program Sri Lanka is pursuing with the IMF’s blessings, said Weerasinghe, 61, a veteran central banker who was called out of retirement in April. “The gradual buildup of reserves is one of the key objectives of the IMF program going forward,” he said.

Until the IMF money starts flowing, he added, “we will not get any external financing from anyone.”

Crossing that threshold, however, depends on the island nation’s three largest foreign bilateral creditors: China, Japan, and India. Colombo has been forced to plead with them for restructuring after the government of former President Gotabaya Rajapaksa confirmed in May that Sri Lanka had run out of dollars to pay its foreign lenders, precipitating its first sovereign default since independence from the U.K. in 1948.

NIKKEI Asia, quoting well-placed government sources, said President Ranil Wickremesinghe’s administration is focused on securing “creditor assurances” in behind-the-scenes talks with these lenders. Wickremesinghe, who doubles as the finance minister, was chosen by the Sri Lankan parliament to finish Rajapaksa’s term after the latter fled the presidential palace in July in the wake of unprecedented public rage triggered by scarcities of food, fuel, and pharmaceuticals in the import-dependent country.

At the end of 2021, as the economic crisis began to bite, total external debt stood at $47 billion in what was an $81 billion economy. According to Sri Lanka’s Finance Ministry, China accounts for 52% of the total bilateral debt, followed by Japan at 19.5% and India at 12%.

Meanwhile, the Hindustan Times said Sri Lanka has headed for major political turbulence ahead as it will not be able to secure the much-needed IMF loan in December for its main ally and debtor China, which was involved in the 20th Party Congress and is still to initiate a dialogue on debt restructuring with the island nation.

According to financial analysts based in Washington, Sri Lanka likely will miss the December IMF deadline and will have to wait until March 2023 to secure a USD 2.9 billion loan from the lending institution in eight equal tranches. In the meantime, the Sri Lankan debt has increased further due to forex depreciation, a deep recession, and a burgeoning fiscal deficit. Since the end of 2021, inflation has considerably eroded the real value of domestic debt.

While debtors India and Japan have already initiated a dialogue with Colombo on debt reconciliation and restructuring, China has yet to engage in the dialogue, as Beijing was involved in the 20th National Party Congress and had little time for client state Sri Lanka. The total debt of the island nation was USD 36 billion at the end of 2021. Of this, Sri Lanka owes USD 7.1 billion to China or 20 per cent of its debt. The total public debt, which was 115.3 per cent of the GDP at the end of December 2021, has now gone up to 143.7 per cent of the GDP by the end of June 2022. Of this, the bilateral debt has climbed from 12.7 per cent of the GDP to 20.4 per cent of the GDP. On October 31, 2022, Sri Lankan President Ranil Wickremesinghe went on record stating: “Now, this is the process; we had to move.” If we can move forward and come to an agreement by December, which means coming to an agreement by mid-November and going up to the IMF Board in mid-December, we will gain a big advantage. However, I’m not sure we can do it because, in China, the focus has already begun following the party conference. However, we must aim to have it by January.

Sri Lanka is in need of a bridge loan of USD 850 million to survive until the next IMF board meeting in March and avert burgeoning public discontent with the Ranil Wickremesinghe administration.

Delays by the government in providing the essentials for the consumption of the general public may give some leverage for the leftist JVP (Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna) and Front Line Social Party (FSP) to gain political mileage. It may create havoc with public protests akin to the Aragalaya in July 2022. The main opposition party, SJB, seems more responsible and less likely to rouse public protest when the government is going through a historically difficult period.

The pertinent question that remains to be answered is who would grant the USD 850 million bridge financing facility to help the government survive.

The economic fallout in Sri Lanka is mainly due to mismanagement, poor fiscal discipline, and corruption by the previous Gotabaya-Mahinda Rajapaksa regime, which secured a massive Chinese loan to construct the 900-megawatt Norochcholai Coal Power Plant apparently at 11 per cent interest. The projects undertaken by Sri Lanka have created an economic black hole with no signs of recovery, at least for the next five years.

Besides, India has already had two rounds of talks in respect of debt restructuring, while China has been dragging its feet for reasons best known to itself. India is also in discussion with Japan to explore an early solution.

Sri Lanka owes nearly USD 1.7 billion in bilateral debt to India, with another USD 4 billion in emergency assistance, as the Modi government has gone out of its way to keep the island nation afloat, the Indian media said.

It also said this is even though Sri Lanka is still playing around with India’s adversaries, China and Pakistan, in the Indian Ocean region. Perhaps Sri Lanka is waiting for China to lift its “zero-corruption” policy and allow Han Chinese tourists to spend money in the island nation to revive its economy. The political and economic future of Sri Lanka is very bleak.

Meanwhile, the Hindustan Times reported that because Sri Lanka has yet to initiate talks with the Xi Jinping regime, the chances of the IMF executive board approving a USD 2.9 billion extended fund facility to the deeply indebted island nation this month are virtually nil.

Putting equal onus on the rich global north and the developing global south, the Paris Club creditor nations are proposing a 10-year moratorium on Sri Lankan debt and another 15 years of debt restructuring as a formula to resolve the current financial crisis in the island nation.

While the Paris Club is still to formally reach out to India and China, two of Sri Lanka’s biggest creditors, with Beijing holding near 50 percent of external debt, Colombo on its part is still to initiate a formal dialogue with the Xi Jinping regime, and the chances of getting an extended fund facility of USD 2.9 billion approved from the IMF executive board this month range from very low to non-existent. This means that Sri Lanka will have to wait for the March IMF meeting before any aid is extended by the Bretton Woods institution.