All stories have their heroes and villains. During the Welikada Prison massacre of July 1983 in which 53 Tamil prisoners lost their lives, there were few prison officials who put their lives on the line to protect the Tamil inmates while there were the others, who by their complicity, encouraged the attackers and failed in their duties by not taking timely measures to protect them.

The killings inside the prison took place on two days with 35 inmates killed on 25 July and 18 others on 27 July. That week, 38 years ago, mayhem was unfolding outside the prison walls too with senseless killings, looting and arson attacks taking place against Tamils, in a month that has since come to be known as ‘Black July.’

The Presidential Truth Commission on Ethnic Violence (1981-1984) appointed by President Chandrika Kumaratunga in 2001 said the murder of the Tamil prisoners within the well-secured precincts of the Welikada Prison and the traumatic experience of those who escaped death would ‘constitute the most agonising moments of challenge to the collective conscience of our Nation.’ In this case, like with many similar extra judicial killings that have taken place in the country since, no one was held accountable, none prosecuted, and the case closed with the State settling the civil lawsuits filed by relatives of some of the victims by paying compensation without admitting liability.

The Commission recorded evidence from survivors of the massacre, prison officials, human rights and civil rights activists and other witnesses to piece together the terrifying atmosphere within the prison during the dark days in July 1983 and how apathy by the Government and some prison officials led to the massacres which would have been averted had they acted on time.

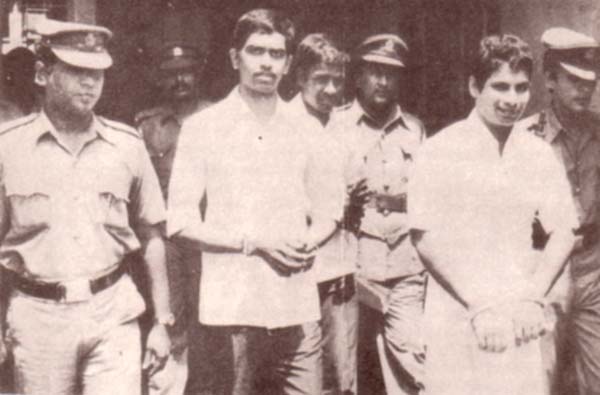

The first massacre on 25 July took place within wing ‘B3’ of the Chapel section of the Welikada Prison where, most prominent among the inmates, was Selvarajah Yogachandran alias Kuttimani who was serving a death sentence for the killing of a Police Constable while concurrently serving another sentence for a bank robbery.

Sarvanaperumal Yogarajah who was held in wing ‘C3’ on the ground floor of the prison and escaped the massacre by feigning death were among those who testified before the Commission which was headed by retired Chief Justice S. Sharvananda with S.S. Sahabandu P.C. and M.M. Zuhair P.C. as its members.

The prisoners were aware of the unrest that had begun at Borella on the evening of 24 July where large crowds had gathered for the cremation of 13 soldiers who were killed in a landmine explosion in the north the day earlier and there was a sense of foreboding among the Tamil prisoners that they could come under attack.

On the afternoon of 25 July, the prisoners in wing ‘C3’ could hear loud sounds of people walking around and shouting but could not see what was happening within wing ‘B3’ where the first massacre was underway. Sometime later Yogarajah had heard the loud cry, “Kuttimani killed” in Sinhala. He could also hear the commentary of some of the inmates whose cells were near the lobby area and could see through the iron bars the bodies of the prisoners who had been battered by fellow inmates being dragged out to the open yard in the prison.

While the attacks were underway in wing ‘B3’, some other prisoners were trying to break open the gate that led to wing ‘C3’ where the witness was being held but a single prison officer had stood between the Tamil prisoners and the attackers, having hidden the keys of the cell in the toilet and standing guard until those trying to break in left the area.

However later two of the attackers who were on the upper floor, presumably, because they had failed to get past the guard, had broken through the wooden floor above the corridor and come down into wing ‘C3’. Having come they appeared to have changed their minds or been prevailed upon by the guards in the corridor to get away, that they shouted at their accomplices upstairs not to come down through the hole and told some of the men in the cells, “We have killed enough today, we will come back another time.”

Things were quiet the next day as all the inmates were kept locked up, but this was to change a day later. In the middle of the night of 26 July, prison officers had come to wing ‘C3’ and asked the 28 Tamil inmates there including the witness to collect their belongings and come along without making a noise. They were relieved thinking they were being transferred out of the prison but instead were moved to the Youth Offenders (YO) Block which is a separate area within the prison compound. They were then locked up on the ground floor of the building.

Nine other Tamil detainees who were held in the YO block had been moved to a dormitory upstairs to make room for the 28 who were transferred from wing ‘C3’. Yogarajah said that though they were moved to a new block, they were anticipating another attack and decided to improvise weapons for self-defence using whatever was at their disposal including plates, buckets and even saving the curries served to them.

Among the nine prisoners who were moved upstairs, there were three Christian priests and hence they were provided with a table and some chairs to use for mass. They had broken the table and chairs and fortified themselves as best as they could anticipating the worst.

On the afternoon of 27 July, those in the YO block had heard the sound of a mob on the rampage approaching the building. Each one of the Tamil detainees had fought back, some were killed but Yogarajah had feigned death and managed to escape. A few days later, he and the other survivors were transferred to the Batticaloa Prison.

The Commission observed that while there were individual officers who attempted to restrain and bring the situation under control, there is material to conclude that certain prison officials were complicit in the attacks carried out on the Tamil prisoners on the two days and there were no organised measures taken to deal with the situation.

The Commission also said that army personnel who were on guard outside the Welikada Prison had refused to help prison authorities who sought their intervention saying they had ‘no orders from headquarters’ while witnesses told the Commission that soldiers were heard shouting ‘Jayawewa’ when news broke of the killings of the Tamil prisoners.

Civil Rights Movement (CRM) General Secretary Suriya Wickremasinghe was among a few who worked tirelessly to locate and interview witnesses to the incidents and ensure high standards were maintained during the interview process so as to elicit the truth by testing the veracity of each version with the other. She and a few others also travelled to Madras (Chennai) in South India to interview some of the survivors.

In her testimony before the Commission, Wickremasinghe said she heard from one of the witnesses how an Assistant Superintendent of Prisons who was on duty at wing ‘C3’ on 25 July put his foot on the padlock of the door that led to the cell and stood up to the attackers thus preventing the killing of Tamil prisoners in that cell on the first day while another witness spoke of two jailors who threatened the Tamil prisoners (he could not identify them) telling them, “Let’s see (balamu), today is your last day.”

She also said the conduct of the army personnel on duty outside the prison on 25 July was ‘very strange’ and they seemed to have obstructed every attempt to control the situation and to let the injured be taken for treatment.

The CRM assisted in filing 30 civil cases in the District Court for damages on grounds the State failed to take care of the prisoners. The State settled all the cases by paying compensation without admitting liability.

The findings of the Commission were a damning indictment of the Government of the day. All evidence relating to the attacks on 25 and 27 July were not placed at the inquest proceedings into the killings, no attempts were made to identify the miscreants and efforts to trace police records turned futile, with the Commission told that the records were untraceable. Attempts to initiate an internal inquiry by the head of the Welikada Prison at the time Leo de Silva too were sabotaged and he was prevented from giving evidence at the inquest by the Magistrate even though he was a key witness.

Of the 72 Tamil prisoners who were at Welikada Prison that week in July, only 19 escaped the massacre. They were transferred to the Batticaloa Prison on 29 July. Some escaped to India in September by breaking out of prison while a few were released sometime later without charges.

In some stories, the villains go unpunished, the heroes go unrecognised and the victims forgotten. The story of the Welikada Prison massacre of 1983 is one such, but also one of many such unfortunate events the country has seen. Nearly four decades later, there are few lessons learnt from such tragedies.

SL far from meeting UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners

The Daily FT asked Ambika Satkunanathan, human rights lawyer and former Commissioner of the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka (HRCSL) who led the first national study of prisons at HRCSL if prisons are any safer for inmates today, if there are better protocols in place to keep prisoners safe and the role of the public/civil society in looking at prisoners with the empathy they deserve. Following are excerpts of the interview:

Q: How safe are the country’s prisons for inmates?

To determine whether Sri Lanka’s prisons are safe we have to look at two elements – the conditions in which persons are held and their treatment by prison officials. As the HRCSL’s prison study illustrated, the conditions in which they are held do not meet basic standards and in many instances are inhumane and constitute degrading treatment. For example, at Welikada Prison the entire H Ward building was noted to be sinking on one side, as the building is very old.

The whole building was condemned and abandoned a few years ago but due to overcrowding the ground floor and a half of the first floor were still being used in 2020. Nine or even 10 persons sleep in a cell which is locked at night and hence they have to use a bucket or plastic bag to relieve themselves at night. There is little ventilation or light, and people have to deal with bed bugs, rats, and pigeons, which create an environment that is hazardous to health. Those on death row are held 23 hours in cells that have little light due to which many have problems with their eyesight.

Where the treatment of persons in prisons is concerned, the use of violence to subjugate, degrade, humiliate, and control a person is common. There are instances when I have searched and found persons who were hidden from us because they had been badly tortured the day prior to our visit.

There was an instance where a person was being tied up and assaulted when HRCSL visited, and the officer released the person as soon as he heard HRCSL had arrived. The person came running towards the officers, fell at their feet and pleaded with them to save him. Although the use of violence is common, persons in prison have very few ways of complaining of the ill-treatment and could face reprisals if they do. This is all to say that our prisons are not safe at all.

Q: Are there adequate protocols in place to be followed in case of unrest/attacks on inmates within prison?

To my knowledge there are no formal protocols on how to deal with unrest in prison, and particularly guards, who are at the front line, have little or no knowledge of how to quell unrest or resolve conflict in non-violent ways.

Q: Since 1983, we have had several other incidents where inmates were killed inside prisons but there has been almost zero accountability/prosecution. What role should the state play in such instances?

We have to make a distinction between the state and government. Although there are some legal mechanisms to deal with violation of rights, such as the Convention Against Torture Act, the state itself is tolerant of violence and violence is embedded in many of its structures and processes. As long as we don’t acknowledge or address structural violence, it will be impossible to make prisons or even society less violent.

At the same time, successive governments have had scant respect for the rule of law and impunity is entrenched in Sri Lanka. Many governments did not even symbolically adopt a zero-tolerance approach to torture or extra-judicial killings. Even those that claimed to have a zero-tolerance policy didn’t always practice what they preached and hence state officials knew they would not be held accountable. The state (and of course the government) nearly always protects its own.

Q: Is Sri Lanka any closer to achieving the objectives of the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (Mandela rules)?

Successive governments ignored the penal sector because prisons are viewed as places where you lock up persons considered undesirables, throw away the key and forget about them. This is easily done because the prison population consists mostly of the poor and marginalised. Because those in prison are viewed as ‘criminals’ they are not considered persons who have rights but as second-class citizens.

Our aim should not be to build more and better prisons. Our aim should be to reduce the number of persons being sent to prisons and close prisons. For this we need criminal justice reform as well as socio-economic policy to address the drivers of crime. We need responsible policymaking on allocation of public resources. For instance, we spent over $ 100 million to build the Lotus Tower but don’t think an equal amount should be invested in social protection mechanisms, such as employment and preventing homelessness to prevent the society to prison pipeline.

Q: What roles can the civil society/public play to build empathy for prisoners?

The public and civil society have a critical role to play in reducing the society to a prison pipeline and helping people break out of the cycle of poverty, violence, and imprisonment. Most often politicians point to public demand for tougher punishments for crime to justify increasingly punitive measures. The public supports such Government measures because they don’t see the state’s failure to prevent crime, nor do they link that to the state’s failure to address the socio-economic drivers of crime.

Instead of demanding tougher punishments the public should demand the Government invest in social protection and support mechanisms. Also, people don’t seem to be aware that the deprivation of liberty is supposed to be ‘the’ punishment. Once deprived of liberty you are not supposed to be deprived of everything else. In Sri Lanka most think a person has to be punished in prison and isn’t deserving even of decent food or a bed. What we need is a humane approach that recognises persons in prison too have dignity and rights.

A simple way to start humanising persons in prison is to be mindful of the language we use. Often people don’t realise that certain terms which we commonly use are dehumanising. An example is the term ‘inmate’. Instead of saying inmate or prisoner we can use incarcerated people or people in prisons. The change in how we use language is something that even I had to do consciously because we have normalised the use of these words to the point that we don’t realise how they enable the dehumanisation of persons in prisons.