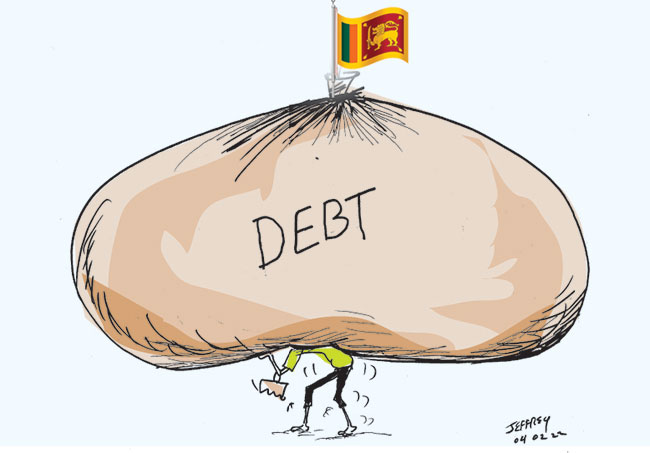

Having hit a roadblock with international bondholders, uncertainty looms over the economy of crisis-hit Sri Lanka and an upcoming review by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), experts warn.

The South Asian island country announced on Tuesday that it has failed to strike an agreement with international bondholders on restructuring more than $12 billion in debt, a mandatory requirement set out by the IMF.

Colombo-based economist Talal Rafi explained that with Sri Lanka still in default status and facing uncertainty regarding credit ratings and foreign investment, the economic fallout could be significant. “The larger impact is the uncertainty as no one knows what the deal will be for them to plan anything,” he said.

In March last year, the IMF’s board approved a $2.9 billion bailout package under a 48-month arrangement under the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) to support Sri Lanka’s economic policies and reforms. Sri Lanka is currently on its second review and is awaiting board approval for a staff-level agreement reached in March this year. Since 1965 to 2016, Sri Lanka has had a total of 16 programs with the IMF and the current program with IMF is the seventeenth.

The delay in reaching an agreement could also affect Sri Lanka’s upcoming IMF review, which is scheduled for June, Rafi said. “As debt restructuring is a key condition for the IMF, it would have an impact on the time taken for board approval.”

The program specifically supports Sri Lanka’s efforts to restore macroeconomic stability and debt sustainability, safeguard financial stability, and enhance growth-oriented structural reforms. In April 2022, the country defaulted on its foreign debt for the first time, triggering the worst economic crisis in its history. According to official data, Sri Lanka’s gross official foreign currency reserves inched up to $4.5 billion million in February.

Moreover, the nation’s impending presidential election piles pressure on the government to accelerate the negotiation process, raising concerns about the sustainability of any deal struck hastily under such circumstances. “In a rushed environment, there is a chance an unfavorable deal may be struck, where the debt repayments agreed may be unsustainable for Sri Lanka to pay in the coming years which could lead to a second default,” Rafi noted.

Sri Lanka is expected to hold its presidential election between September and October. In 2019, Gotabaya Rajapaksa was elected as president, but he was forced to resign due to mismanagement in 2022, which led to Ranil Wickremesinghe taking over. Presidential elections take place every 5 years.

Despite the stumbling block, Sagala Ratnayaka, Sri Lanka’s national security adviser and chief of staff to the president, said “there is no snag, but the discussions will continue.”

He explained that the government couldn’t come to a “settlement” specifically in two areas of the counter-proposals submitted to the government by bondholders. However, Rathnayaka emphasized the government’s commitment to continuing discussions and involving all stakeholders, including bond advisers and representatives from the IMF.

Shehan Semasinghe, Sri Lanka’s finance minister, said in a statement on Wednesday, “The next steps would entail further consultation with the IMF staff regarding assessments of the compatibility of the latest proposals with program parameters.” He added, “We hope to continue discussions with the bondholders with a view to reaching common ground ahead of the IMF board consideration of the second review of Sri Lanka’s EFF program.”

However, Sergi Lanau, director of global emerging markets strategy at Oxford Economics, said that debt restructuring is progressing slowly everywhere. Ghana, for example, defaulted in December 2022 and is still negotiating, he said. “I don’t think there are widespread expectations of a quick agreement in Sri Lanka.”

Reflecting on the lack of trust and transparency that has characterized the negotiations from the outset, W.A. Wijewardena, a former central bank deputy governor, said, “The outcome involving the failure to reach agreement is not unanticipated because neither party had any intention of reaching out to the other.”

According to Wijewardena, the trust necessary for a fair negotiation was absent. “Now it seems both parties are asking for the pound of flesh which isn’t available for delivery to the other party.”

Source: Nikkei Asia