The death of 23-year-old Mano Yogalingam, a Sri Lankan Tamil ‘asylum-seeker’ on a ‘bridge visa’ in Melbourne, Australia, after he set himself afire should have shocked human conscience in the western hemisphere. It begins with the question how and why a 13-year-old in 2013, when he landed in Australia as a refugee, should ever have left Sri Lanka full five years after the end of the war, when normalcy had almost returned to the war-torn nation.

But the question is also about the overt concerns of the western world to allegations of human rights violations and ‘war crimes’, as is the case with Sri Lanka. However, Mano’s self-immolation in a skating rink does not seem to have triggered well-meaning human consciousness in the western world. Media reports quoting Australian authorities have said how Tamils in Sri Lanka ‘face a low risk of official or societal discrimination’ and ‘a low risk of torture overall’.

Australia is accepted as a ranking member of the western world in other matters, starting with the four-nation Quad, and the three-nation AUKUS, for strategic reasons aimed at China, yes, but on other matters, the US has a combination of other western friends and allies, whose views on human rights in third countries, particularly Third World countries, are conditioned by their own local conditions.

Thus you have Scandinavian countries, and those like Germany, all of them in post-War Europe, telling South Asian families in their midst, how their children had to be brought up in the new environment. You can call it homogenisation of cultures and traditions by force, playing on the greed, avarice and vulnerability of those parents wanting a western identity, green-card and citizenship.

All their efforts to be what they are not, subsumes their original identity and culture, and they don’t care. They are in effect and also in fact ‘economic refugees’, not ‘political refugees’, as they want the West to believe. It was the case with many, if not most of them, even at the height of the ethnic wars in Sri Lanka, for instance.

The West too could do with their labour but without the hang-over of their politico-cultural past in a distant country. Allegations of human rights violations on the home-front also ensured that the merged their cultural identities with their next-door neighbours and the larger community they lived in.

Threats of taking away their children for better care (or, bitter care?) were a part of the process. An occasional demonstration of the institutionalised legal threat helped, even though that might not have been the original idea.

Different world

Today, when Sri Lanka is having the most challenging presidential elections, post-independence, the West is behaving as if they are in a different world, rather a different universe. Or, they seem to think that Sri Lanka does not belong to the Earth that they all live in.

Else, you cannot explain or appreciate why not one of those nations has appreciated and applauded every Sri Lankan and the larger Sri Lankan system for a relatively smooth-transition of elected national leadership with another, under another schemed prescribed by the very same Constitution, and the consequent return of normalcy, effortlessly. Through the past two years, post-Aragalaya, no one has talked about the mass-protests of 2022, nor have they threatened the State and the people with yet another of the kind.

If this is the western attitude towards democracy in the country, it is anybody’s guess why the Sri Lankan Election Commission (EC) should be bending backwards to invite a European Union (EU) team of poll observers to oversee the ongoing process, when on other matters Sri Lankan, all arms of the State swear by ‘sovereignty’, et al? It is equally so, why Foreign Minister Ali Sabry should be sparing time for the EU observers when he has squarely told the UNHRC, for instance, that the latter’s way of proceeding with ‘war crimes’ and ‘accountability issues’ interferes with and challenges the nation’s sovereignty, to begin with.

That way, Minister Sabry, and more so, the ‘independent’ Election Commission, and through them both the Sri Lankan State, have compromised the nation’s sovereignty, unlike in the case of the UNHRC and other UN affiliates, where ‘shared sovereignty’ of a kind has become an acceptable international premise applicable to all member-states, equitably if not equally. In such a scenario, what kind of ‘independence’ does the Election Commission assume that it enjoys – outside the Constitution, and not inside, where it still has its say and way.

Evaluating the vote

Leave the UNHRC, which is an extension of the UN but without the facility of power-play through the veto-vote of five designated member-States, and even the western-funded outsider-affiliates of the Amnesty and Human Rights Watch (HRW) kind, you now have the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) commenting on the continuing plight of the families of the Tamils missing in the ethnic war that ended 15 long years back. The ICRC in particular might not have exceeded its mandate, so to say, but their men on the ground at least should have known the politics of it all.

More importantly, the ICRC and HRW reports seemed to have been timed for the presidential poll, as if seeking to influence the Sri Lankan vote, one way or the other. It is unlike the UNHRC session, commencing on 9 September, where Sri Lanka has become a permanent agenda-item, much longer than the Ukraine War and even the West Asia tangle, if you forgot the past years when there was relative peace on the Israeli front, or Israel’s fronts within and with its disquiet citizens / neighbours.

The revived / renewed UNHRC vote on Sri Lanka will come up for vote in the first week of October, but only after the results of the 21 September presidential polls are known. This means, whoever is elected President, including the incumbent, would seek and possibly obtain more time to address the issues highlighted in the new draft. Minister Sabry having dismissed the so-called ‘findings’ in the initial High Commissioner’s report to the Council, now in circulation, every future government that is predictably in place, post-results, would (or, would have to) stick to the same.

The Sri Lankan interest in the matter will then be confined to the nations that voted for the US-led Core Group’s resolution, who voted against it (and in favour of Sri Lanka) and who all abstained. Given the current mood and trend, the nation as a whole will be watching the performance of the northern Indian neighbour in particular. Having backed the US resolution after ensuring amendments in the first year, India has mostly been ‘abstaining’ from the vote through the past decade.

Cultural invasion

For their part, at least two front-line candidates, in JVP’s Anura Kumara Dissanayake and SLPP’s Namal Rajapaksa – the former supposedly the front-runner, and the latter believed to be the last of the four in the top-rungs – have clearly stated that they would not allow any harm coming to the Sri Lankan soldiers in the name of ‘accountability issues’ of the UNHRC kind. Incumbent government of Candidate Ranil has already rejected the UNHRC report officially. The other front-runner, Sajith Premadasa too is expected to do so, when push comes to shove.

There is of course a ‘common Tamil candidate’, who is not unlikely to obtain more Tamil votes than some had thought earlier. But the sponsors of Ariyanethiran have been clear from day one that he was contesting not to win, but only to send out a ‘strong message’ to the Sinhala South and also to the international community. None of the other front-line candidates as yet, at least Namal’s SLPP has since stated that the presence of a ‘common Tamil candidate’ would only negatively impact ‘reconciliation efforts’ (?)

The most serious of all post-war reconciliation efforts began and ended with the forgotten TNA’s months of negotiations with the war-victorious regime of President Mahinda Rajapaksa. The latter had a global stake for being known as much as a peace-maker as a war-victor against terrorism of an unprecedented scale. The TNA also knew that if post-war Mahinda could not tell the Sinhala nationalists that he would not compromise on the nation’s sovereignty, none after him would be able to do so.

Yet, when it came to that, ill-advised as the TNA was, they said the unthinkable: that they were behind the US-led core group moving the UNHRC on ‘war crimes’ and ‘accountability issues’ as far back as 2012. That was the end of it. All later-day attempts for a new Constitution as Prime Minister Ranil promised during the forgettable Government of National (dis-) Unity, 2015-19, were farcical at best, and the TNA too played along, knowing full well where it would end.

Today, in a way, all promises of a new Constitution, whether from Ranil, Sajith or Anura, are not going to meet the Tamils’ expectations – which under the constitutional scheme comprises re-merger of the North and the East, and also a federal structure, which is just not going to happen. But then, the divided Tamil polity, starting with the ‘common candidate’ movement is not saying anything, at least for now, about the ‘accountability issues’, as enunciated for them by the rest of the world. Nor have they said a word during the poll campaign about the ‘cultural invasion’ of the Tamil areas and Tamil symbols, not just by Sinhala-Buddhist hard-liners but the Sri Lankan State.

Greater consolidation

On the face of it, the ICRC and HRW observations, carefully timed as they might have been, may trigger a greater consolidation of Tamil votes behind the common candidate. The same cannot be said about the UNHRC session, which is pre-scheduled for particular months/weeks in the year. Only the presidential poll has coincided with it this time, not that anyone in Colombo expected anything else from the pen of the High Commissioner.

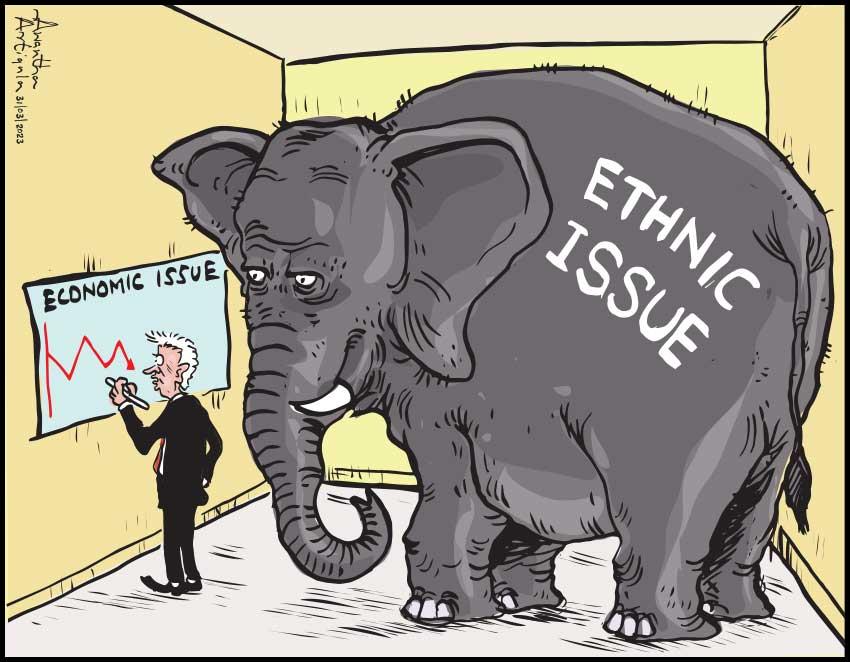

Whatever that be, any debate nearer home on these issues, especially in the face of the UNHRC session beginning next week, could lead to a sudden interest in an ethnic solution, and the larger political issue(s) that have not found their customary place and pace in the nation’s electoral process. That is because the economy, both national and personal, is of greater and immediate concern for every stake-holder, big and small, governmental and individualistic.

But any overnight pick-up in political momentum could have the potential to reshape the electoral campaign in ways not thought of since, this time round. If the debates were to trigger Sinhala-Buddhist nationalist sentiments as never before this time round, the question is if it could reset the national agenda at the last-minute when every candidate and political party is talking economics, which many of them just do not know, or even claim to know.

That is the kind of situation some of the candidates may be hoping for – and others may not wish for. And thereby may hang another tale!

(The writer is a Chennai-based Policy Analyst & Political Commentator. Email: sathiyam54@nsathiyamoorthy.com)