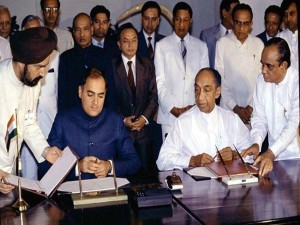

Much concern is now being shown by political parties representing the minority (numerical) ethnicities of Sri Lanka over the 13th Amendment to the Constitution. As is well known it is the 13th Constitutional Amendment which ushered in a certain quantum of devolution to the country through the setting up of Provincial Councils. 13 A itself was due to the historic India-Sri Lanka agreement signed by Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and Sri Lankan President Junius Richard Jayewardene on July 29th 1987.

Several political parties of the Sri Lankan Tamils, Muslims and Hill Country Tamils met in Colombo on December 12th and engaged in discussions aimed at demanding full implementation of the 13th amendment. A news report filed by “The Hindu”s Colombo correspondent Meera Srinivasan provided pertinent details of the the Colombo meeting. Here are a few excerpts –

“India has repeatedly asked the Sri Lankan leadership to ensure the full implementation of the 13th Amendment. While Colombo has in turn given many assurances to “go beyond” the legislation, to ensure meaningful devolution, “that has not happened so far,” said senior Tamil politician and Tamil National Alliance Leader R. Sampanthan. “We have gathered today from different political parties to discuss the situation. We exchanged our views on the subject, and will be taking this discussion forward,” he told a press conference, following the MPs’ meet at a Colombo hotel on Sunday.”

“There is now talk of a new Constitution, but simultaneously we see the government’s efforts such as ‘One Country One Law’,” the 88-year-old Trincomalee parliamentarian said, of an ongoing initiative of the government that critics fear might further impair even the limited legislative powers of the Provincial Councils”.

“Sri Lanka’s nine Provincial Councils are defunct for about two years, after their terms lapsed in 2018 and 2019. “Meanwhile, the Centre through various presidential task forces is trying to snatch our powers. If that has to be stopped, we must emphasise our rights highlighting what is guaranteed in our Constitution,” said Rauf Hakeem, Sri Lanka Muslim Congress Leader and legislator.”

“The parliamentarians will finalise a “comprehensive document” by December 21, said Mano Ganesan, Leader of the Tamil Progressive Alliance that represents Malaiyaha Tamils.“We are challenging this government and asking them to fully implement what is already in our Constitution. Nothing has changed in this country 12 years after the war ended. Our message is not only to the Sri Lankan leadership, but also to India, the international community and UN bodies,” he said. As a signatory to the Accord of 1987, “India has an obligation,” Mr. Ganesan added. The final document coming out of the discussion would also be sent to Prime Minister Narendranew Constitution Modi, according to the organisers.”

It is indeed commendable that the Tamil and Muslim parties are displaying interest in preserving the 13th amendment and seeking full implementation of its provisions. Recent happenings like the appointment of the “One Country,one Law”Presidential Task Force headed by controversial Buddhist monk Gnanasara Thero and the moves underway to promulgate a new Constitution have increased apprehensions among the Tamil and Muslim parties. There is fear that the substance and unit of d would be eliminated or drastically eroded.Hence the envisaged appeal to India to safeguard the Provincial councils and ensure full implementation of powers provided by the Constitution.Better late than never!

Seeking India’s Help

The potential danger to the 13th Constitutional Amendment and the Provincial council scheme under the Rajapaksa regime was anticipated by this writer even before the 2020 August Parliamentary elections took place. “TNA Must Seek India’s Help To Protect 13th Amendment” was the heading of an article written by me that was published in the “Daily Mirror” of July 25th 2020. In that article I appealed to the Tamil National Alliance – the premier political configuration of the Sri Lankan Tamils- to take steps with New Delhi’s help to safeguard 13 A.Here are some relevant excerpts –

“The TNA does not seem to have realised that the Rajapaksa rationale for a new Constitution and the Constitutional reform aspirations of the party are incompatible at the present juncture. The Rajapaksa regime wants to reduce or do away with the powers of the Provincial council while the TNA like Oliver Twist wants “More”, as it is of the firm opinion that the powers of devolution available is inadequate both in quantity and quality. The TNA manifesto illustrates this clearly. “

The TNA’s election manifesto for the 2020 parliamentary polls stated “the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution of Sri Lanka is flawed in that, power is concentrated at the centre and its agent, the Governor.” The TNA manifesto went on to say “It is through a constitutional arrangement on the model of federalism within a united Sri Lanka that the legitimate aspirations of the Sri Lankan Tamils and other Tamil speaking inhabitants of the northern and eastern parts of the island could be met. In fact, such an arrangement has become indispensable for their survival.”

“The TNA or for that matter the Tamil people are well within their rights to demand greater devolution or federalism. They are even entitled to exercise their inalienable right of self-determination and espouse secession or seek a separate state. The problem is how do you achieve it when the overwhelming majority in the country are against it? The harsh reality that the Tamil people have experienced since independence from the British is that, the Sinhala people were not for federalism or even maximum devolution. In such a situation, a pragmatic course to follow would have been adherence to Prussian Statesman Prince Otto Von Bismarck’s saying “Politics is the art of the possible, the attainable — the art of the next best”.

“Far Worse”not

“Next Best”

“This did not happen with the Sri Lankan Tamil political leaders. Instead they opted for secession which resulted subsequently in an armed struggle. Sri Lanka was embroiled in a three decade long civil war that left the Tamils a battered and shattered people. Instead of opting pragmatically for the “next best”, the Tamils chose to pursue what could be termed with the wisdom of hindsight, as a “far worse” one.

In a political environment where the objective conditions for gaining federalism or devolution did not exist, how was it possible to create a conducive climate for secession? Likewise, in a situation where the ruling regime wants to abolish or minimize the little devolution that is available, would it be possible to engage in meaningful negotiations aimed at maximizing devolution through Constitutional reform?

“This does not mean that the Tamil people have to meekly accept the diktat of the Rajapaksa govt. and cave in subserviently. Injustice and oppression has to be resisted and fought against through legitimate avenues. The search for greater devolution must not be abandoned totally. At the same time, one must be realistic. “

“Instead of day-dreaming about getting quasi-federalism through discussions with the Rajapaksa regime, the TNA needs to safeguard and consolidate what has been gained so far. In short, the TNA and the Tamil people have to work with what has been attained and strive further for the attainable, instead of neglecting what is available on ground and yearning for the desirable that is unattainable.”

“The need of the hour is to preserve and protect what has been gained. The govt. plans to abolish or emasculate the 13th amendment and provincial councils, must be foiled. What is necessary at this point of time, is to safeguard the 13A and provincial council scheme.”

This writer is somewhat glad that the Tamil and Muslim parties have adopted a position seeking to protect and preserve the 13 A brought about by the Indo-Lanka accord.It may be appropriate at this juncture to briefly examine the situation that prevailed in 1987 when the Indo-Lanka Accord was enacted and the events that led to it. I have in the past written extensively on these matters and would therefore rely on some of my earlier writings in this regard.

Benign Intervention

Indian involvement in the affairs of its neighbours has been described as “benign intervention” by Indian academics and analysts. Benign intervention also served India’s interests in the region. Such is the nature of international relations. All countries have their own interests at heart and smaller entities identifying common interests with larger entities and harmonising accordingly have greater chances of bettering the prospects for themselves. In the case of Sri Lanka the twin tenets of basic Indian policy was preserving the unity and territorial integrity of Sri Lanka on the one hand and ensuring the rights of the minorities particularly the Sri Lankan Tamils on the other.

The 1983 July anti-Tamil pogrom saw more than 100,000 Tamils fleeing to Tamil Nadu as refugees. Several ex-Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) MPs including Opposition Leader Appapillai Amirthalingam took up residence in Tamil Nadu. With more than 100,000 refugees on its soil providing a ‘locus standi’, New Delhi offered its good offices to mediate and bring about a negotiated political settlement. There was an imperative need for India to intervene at that stage.

There were three basic reasons for Indian intervention in Sri Lanka then. Firstly, the Jayewardene Government was spurning “non-alignment” and taking Sri Lanka into a pro-Western orbit. Under prevailing conditions of the day New Delhi feared a Washington-Tel Aviv-Islamabad axis. India needed to bring Sri Lanka to “heel” and keep out undesirable elements out of the region.

Secondly, there was the domestic imperative. There was much concern in Tamil Nadu for the plight of Tamils in Sri Lanka. Tamil Nadu was once home to a flourishing separatist movement. India was concerned about the fallout from Sri Lanka on Tamil Nadu if the conflict escalated here.

The third was the unacknowledged personality factor. It is a fact that basic policy is formulated by the bureaucracy in India and the political executive is guided by it. However individual leaders by force of their personality may effect a change in the style of implementation but cannot effectively change the substance of policy.

“Cow and Calf”

What happened here was that the then Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was not very fond of President Jayewardene or Prime Minister Premadasa. When Indira Gandhi and son Sanjay Gandhi lost the elections in the 1977 March Indian elections, the UNP leaders began saying the “cow and calf” will lose here too alluding to Sirima and Anura. JR cosied up to Indira’s bete noir Morarji Desai. On the other hand Indira enjoyed close rapport with TULF leaders, particularly Amirthalingam. The TULF had loyally stood by her in defeat. This personality factor also played a significant part in the politics of that time.

This confluence of factors deemed it necessary that India:

1. Undertake a “benign” intervention in Sri Lanka to help resolve the ethnic conflict within a united Sri Lanka but in a manner acceptable to Tamils;

2. Force Colombo accept New Delhi’s hegemony over the region and appreciate Indian security concerns;

3. Teach the Jayewardene regime a lesson while rewarding the TULF.

The fundamental difference in New Delhi policy towards Pakistan in 1971 and Sri Lanka in 1987 was that in the case of the former it suited Indian interests to fracture Pakistan and create Bangladesh while in the case of the latter, Indian interests were better served by preventing dismemberment of Sri Lanka and unifying the island.

Two-track Policy

The July 1983 anti-Tamil pogrom created an opportunity for India to step in and offer its “good offices” to bring about ethnic reconciliation. So Gopalaswamy Parthasarathy became India’s official emissary tasked with evolving political rapprochement. But India followed a two-track policy. Tamil militant groups were trained and armed and housed on Indian soil. They were allowed to run political cum propaganda offices in Tamil Nadu publicly.

India’s objectives were clear. New Delhi wanted to use the Tamil militants as a cutting edge to de-stabilise the Jayewardene regime and also exert pressure on Colombo to deliver a political settlement. Once a viable solution was arrived at, the Tamil armed struggle was expected to end. Tamil Eelam was never ever on the cards.But the Tamils were not to be abandoned entirely. India would underwrite a political solution and maintain a physical armed presence in north east Sri Lanka to protect the Tamils and help to implement the political solution.

Meanwhile Indira Gandhi was assassinated and her son Rajiv Gandhi succeeded her. Rajiv’s ascendancy saw the veteran Gopalaswamy Parthasarathy being ousted as India’s special envoy to Sri Lanka on the Tamil issue. Foreign Secretary Romesh Bhandari functioned as emissary. Despite these changes the basic continuity in policy remained.

There were many twists and turns but India’s strategy worked to a great extent. After the military operation in Vadamaratchy in May 1987 it appeared that Colombo was on the verge of wiping out the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). At that stage India demonstrated very clearly to Colombo that it would not be allowed to crush Tamil militancy. India violated Sri Lankan air space and dropped food parcels over the Jaffna peninsula on 4 June 1987.

To his credit Jayawardena read the writing on the wall correctly. He caved into Indian pressure and bowed. The Indo-Lanka Accord was signed on 29 July 1987. That treaty gave India a right to be involved in the affairs of Sri Lanka.

Multi-ethnic, Multi-religious

The Indo-Lanka Accord was not perfect. It did not rectify all problems concerning Tamils. But it provided a good and great beginning. The Indo-Lanka Accord recognised Sri Lanka as a multi-ethnic, multi-religious nation. Thus both the mono-ethnic claims of Sinhala supremacists and the two nation theory of Tamil separatists were negated.

It recognised the Northern and Eastern Provinces as historic areas of habitation of the Tamil and Muslim people where they lived with other ethnicities. Thus the Tamils and Muslim right of historic habitation was recognised but there were no exclusive rights. The north-eastern region belonged to all ethnicities.

Moreover the opportunity to create a single Tamil linguistic province was made available at that time. Both provinces were temporarily merged with the proviso that a referendum should be held in the Eastern province to either approve or reject the merger.

A scheme providing devolution of powers on a provincial basis was brought in. Provincial Councils with powers allocated on provincial, concurrent and reserved basis were set up. Tamil was elevated to Official Language status. All those convicted of “terrorist” offences were given official pardon. All militants who took to arms were given a general amnesty.

13 A Supreme Court Ruling

The 13th Constitutional Amendment was drafted in Colombo. An Indian Constitutional lawyer was consulted in an advisory capacity. Given the opposition mounted by the SLFP and JVP then it was feared that any Constitutional amendment requiring an island-wide referendum would not be ratified if the Supreme Court decreed so.Thus the powers and composition of the envisaged Provincial Councils through the 13th Amendment were somewhat restricted. The Supreme Court allowed it without a referendum because of this. Even then the nine-Judge bench was divided five to four.

New Delhi however extracted a promise in writing from JR on 7 November 1987 that he would devolve more powers to the PCs within a specific timeframe. But events took a different turn and this promise was never adhered to by JR or successive regimes. The LTTE started fighting the Indian Army. This transformed the situation.

Primarily, India was acting in its own interest. There was no “identity” of interests between India and the Tamils but there was certainly a “convergence” of interests between both. But this congruence had its limits.

Using the armed struggle for separatism as a pressuring device or bargaining tool was acceptable. But prolonging the struggle for a separate state in defiance of New Delhi was unacceptable. India was all for autonomy within a united Sri Lanka but opposed to Tamil Eelam.

Pragmatically, the best option was for the Sri Lankan Tamils to hitch their “vandil”(wagon) to the Indian star and accept the settlement provided through Indian efforts. The Tamils had a large support base in Tamil Nadu among fellow Tamils which could have been utilised to pressure New Delhi.If the Tamils were politically astute they could have accepted the accord as a starting point and then gradually enhanced devolution to the point of quasi-federalism. In this exercise, India would have been on the side of the Tamils.

North East “Special Status”

In practice, north-east Sri Lanka would have enjoyed a “special” status. The N-E would be part of a “de-Jure” Sri Lanka but virtually a “de-facto” extension of India. A delicate tightrope walking act was required of Sri Lankan Tamil leaders. If they maintained correct relations with New Delhi and Colombo they could have elicited the best of both worlds for their people. If Sinhala hardliners ruled the roost in Colombo and adopted a confrontation course with India, a Turkish-Cyprus type of de-facto partition may have ensued.

But these things did not happen thanks to the colossal political stupidity and self-centred arrogance of the LTTE. Not only did it target the Sri Lankan armed forces but also took on the Indian soldiers. New Delhi had no choice other than to fight the Tigers. The IPKF-LTTE war altered the flow of events. War has a cruel logic and powerful momentum that changes things utterly. And then the Tigers assassinated Rajiv Gandhi in Tamil Nadu. The rest is history. Those who forget the lessons of history are condemned to remember them again bitterly.(ENDS)

D.B.S.Jeyraj can be reached at dbsjeyaraj@yahoo.com