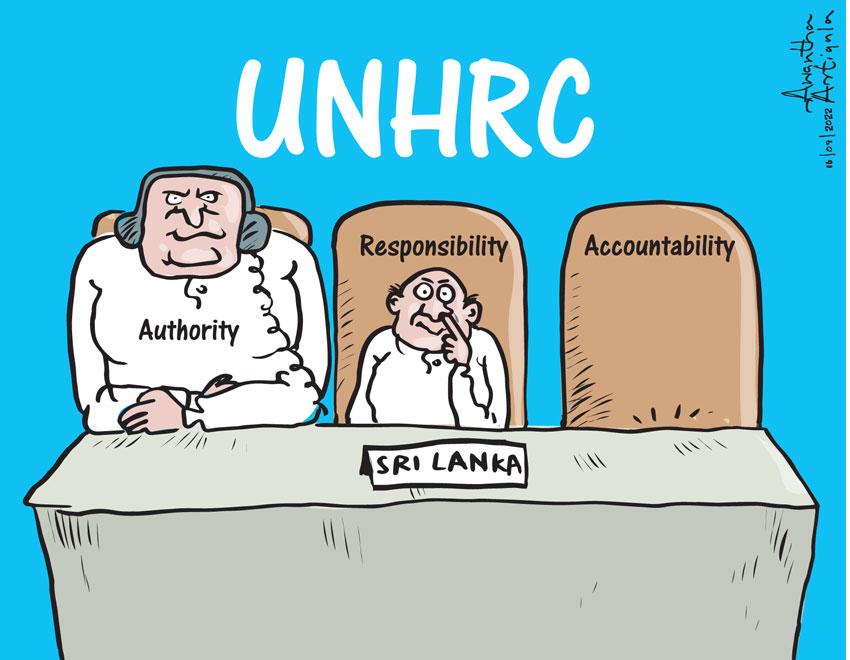

The UN Human Rights Council’s 53rd session will begin On June 19. An oral assessment of the rights situation in Sri Lanka will be made by the Human Rights High Commissioner Volker Türk on June 21. As usual, the Sri Lankan government is going all out to present the case that it has been making sincere efforts to deliver on the promises it had made earlier.

Last week, the President’s Media Division announced an “Action Plan” for ethnic reconciliation that had been drafted at a meeting chaired by President Ranil Wickremesinghe. The plan includes the establishment of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Sri Lanka (TRCSL); the establishment of a National Land Council, and the formulation of a National Land Policy; and the enhanced operations of the Office of Missing Persons (OMP), including their digitization and the issuance of Certificates of Absence for individuals who had disappeared.

But there is nothing new in these decisions. These tasks have been on the agenda for a long time though with little or no progress to show. The most glaring is the idea of setting up a Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Sri Lanka (TRCSL). This idea pops up only when there is a temporary need to mollify the international human rights lobby and is forgotten thereafter.

At a meeting in Pretoria in March, Minister of Justice Wijedasa Rajapakshe and the Minister of Foreign Affairs Ali Sabry discussed with Rolf Meyer and Ivor Jenkins, the contours of the proposed TRC in Sri Lanka inspired by the South African TRC that functioned between 1995 and 2003. Sabry tweeted to say that he got “some very insightful inputs,” and added that “a credible and transparent domestic TRC could be the solution to deal with intrusive and agenda-driven attempts.” He was decrying the UNHRC’s attempts to impose on Sri Lanka mechanisms for achieving ethnic reconciliation based on retributive justice dispensed by a judicial process with foreign participation.

Past Attempts

This is not the first time that Sri Lanka is trying to set up a TRC. It has been attempted before, but only to be abandoned because Sri Lankan society is too divided to make it work. A TRCSL was mooted in 2015, 2018, and 2022 because of pressure from the UNHRC, but was not followed up.

On October 16, 2018, a conceptual framework was submitted to the Lankan cabinet. The concept paper said that the TRC of Sri Lanka (TRCSL) will be established by an Act of Parliament. Justifying this, the concept paper said: “Despite the appointment of numerous ad hoc commissions of inquiry during the past (like the Paranagama Commission, the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission, the Udalagama Commission, Mahanama Tillekeratne Commission) due to failure to implement recommendations made by those Commissions, it has not been possible to successfully prevent recurrence of conflict, or build confidence amongst all the people of Sri Lanka in the efficacy of measures to ensure non-recurrence, advance national unity and reconciliation or identify and undertake administrative reform interventions that may be necessary.”

The concept paper further said that the proposed Act of Parliament would, inter alia, incorporate statutory provisions to appoint a Monitoring Committee which will “enable all Sri Lankan citizens, irrespective of race or religion, including families of police and security forces personnel, civilians in villages that came under attack by terrorists, security forces personnel and police personnel, and all affected persons in all parts of the country, to submit their grievances suffered during any phase of civil disturbances, political unrest or armed conflict that has occurred in the past, to the proposed TRCSL.”

“The proposed TRCSL should have sufficient administrative and investigative powers, including those granted to Commissions of Inquiry. This includes powers to compel the cooperation of persons, State institutions, and public officers in the course of its work. While the TRCSL will not engage in prosecutions, it should be vested with sufficient investigative powers. But the TRCSL’s recommendations shall not be deemed to be a determination of civil or criminal liability of any person.”

The concept paper was referred to the Defense Ministry, but it went no further. In March 2020, the UNHRC reported that the TRC proposal had not made any progress. However, in March 2023, at the invitation of the South African High Commissioner in Sri Lanka, Ministers Wijedasa Rajapakshe and Ali Sabry flew to South Africa to study the South African TRC.

Road Blocks

The delay in the implementation of laudable ideas by Sri Lanka could be attributed to the political and ethnic conditions here. These are not conducive for getting a favorable result from a TRCSL. Sri Lankan society is sharply divided ethnically on issues of right and wrong during the 30-year armed conflict. Unlike the majority Sinhala-Buddhists, the minorities, especially the Tamils, demand retributive justice, and not mere restorative justice which the TRC in South Africa attempted and the Lankan variant hopes to follow.

One of the major disadvantages in Sri Lanka in comparison with South Africa is the absence of an over-arching and towering national leader to move the masses in any particular direction. From 1995 to 2003, when the TRC was functioning in South Africa, it was overseen by icons like President Nelson Mandela and TRC chairman Bishop Desmond Tutu.

TRCSA: Partial Success

However, even under very favorable conditions, the South African TRC (TRCSA) was only a partial success, says Samara Auger, author of “Healing the Wounds of a Nation: The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa.”

Auger says that the TRCSA collected over 21,298 victim statements and over 7000 offenders applied for amnesty. Of these 7000, 1167 were granted full amnesty and 145 partial amnesty. The TRCSA released an interim report in 1998 and a final report on March 21, 2003.

The final report of the TRCSA said that justice is defined not as punishment but as “reparations to victims and rehabilitation to perpetrators.” This was based on the South African native concept of “Ubuntu” according to which sufferings are not “individual” but “collective”, that everyone suffers equally, regardless of class, race or religion. Therefore, people should seek “collective redemption, forsaking revenge in exchange for peaceful alternatives.”

But “Ubuntu” was resisted by the Blacks who thought that equating them with the Whites was grossly unfair. Despite its outstanding leaders, South African society was ethnically divided. A survey of 3700 South Africans conducted in 2000 and 2001 found that 68% of all races found it hard to understand one another and 56% found the other race untrustworthy. Less than one fifth wanted to be friends with members of another race.

However, more Blacks than Whites accepted that the TRCSA promoted reconciliation according to a poll done by Jeremy Sarkin-Hughes, 70% Blacks, 61% Asians, and 37% Whites providing moderate to strong approval of the TRC’s work.

In Sri Lanka, ethnic differences are entrenched. There are sharp differences on what was right and what was wrong during the ethnic conflict. A TRC under these conditions might open wounds rather than heal them. The other question is: Would there be a consensus on restorative justice instead of retributive justice?

More Practical Steps

The more practical alternative would be to take the following steps: release those Tamils jailed for years without cases being filed against them; punish perpetrators of atrocities who are facing credible charges; release public lands acquired by the Security Forces and prevent encroachments on lands by government departments on specious grounds; boost the economies of the war-affected areas North and East.