Sri Lanka has seen long queues to buy essential items amid tight lockdown measures to control the spread of Covid-19.

Shelves at government-run supermarkets have been running low – some even empty – with very little stock remaining of imported goods like milk powder, cereal and rice.

The government denies there are shortages and blames the media for stoking fears.

It follows the government declaring a state of emergency and Sri Lanka’s Central Bank chief stepping down amid a foreign exchange crisis.

What has the government done?

On 30 August, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa announced strict controls on the supply of essential goods.

The government said this was needed to prevent traders hoarding food items and control inflation.

Sri Lanka is grappling with a depreciating currency, inflation and a crippling foreign debt burden. There has also been a slump in foreign tourism due to the pandemic.

The economic slowdown is of particular concern as until recently, Sri Lanka had one of the strongest economies in South Asia.

In 2019, it was upgraded to an upper middle-income country by the World Bank.

But at the same time, the country’s debt burden has also been growing – from 39% of Gross National Income (GNI) in 2010 to 69% in 2019, according to the World Bank.

What’s happened to food prices and supplies?

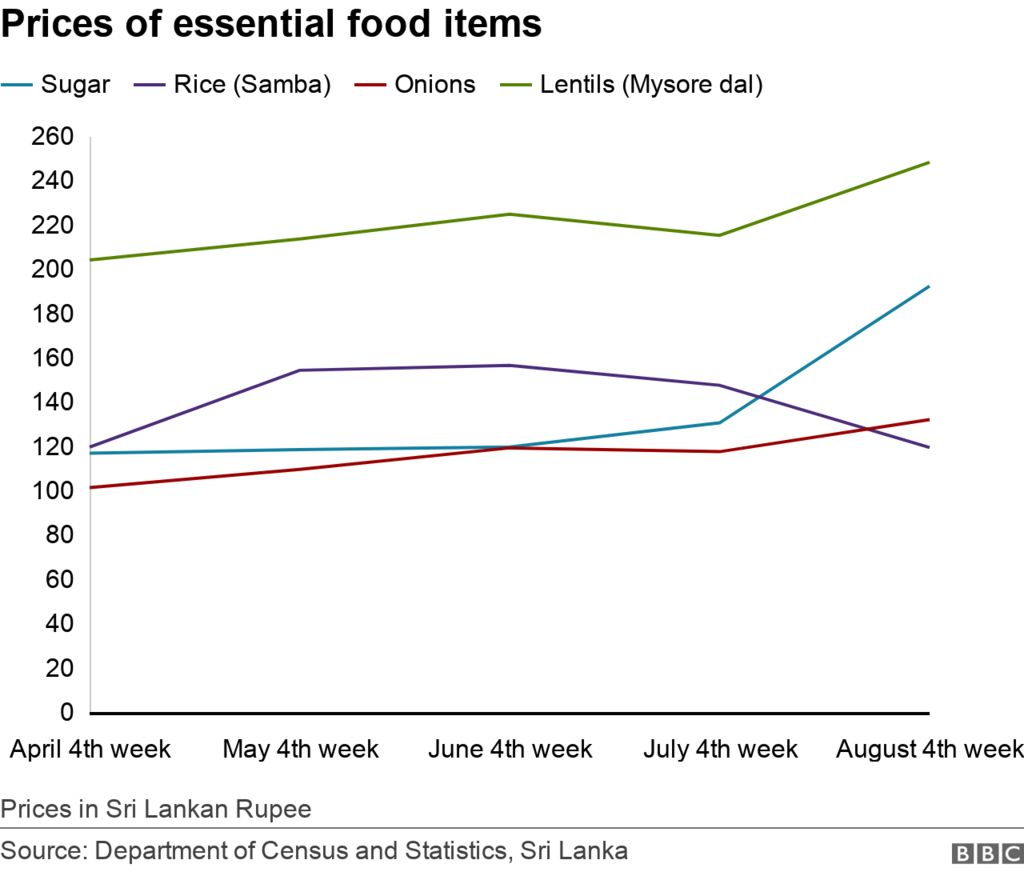

As a result of the economic crisis, the prices of some essential food items have been rising.

In recent months, items such as sugar, onions and lentils have been rising in cost.

Meanwhile, after rising in May, the price of rice fell and has continued to drop following the imposition of a retail price cap from the start of September.

The emergency regulations allow the government to provide food items and other essentials at fixed prices by buying up stock from traders.

In regard to shortages, the country’s finance ministry told the BBC in a statement that these were “artificial”.

“The creation of an artificial shortage by unscrupulous elements will obviously lead to increases in prices of those items.”

The government has strongly denied that shortages are imminent.

“We can give a categorical and firm assurance that all essential items would be readily available at all times,” the finance ministry said in its response to the BBC.

Members of parliament critical of the government’s policy have said other laws to monitor hoarding and price rises were already available and the decision to declare an emergency was made in “bad faith”.

”[The crisis] is merely a manifestation of a power struggle where the president and government are callously risking lives of citizens, with the hope of consolidating power,” Eran Wickramaratne, from the opposition SJB party, said in the Sri Lankan parliament.

Could organic farming be to blame?

In April, the government banned imports of chemical fertilisers, pesticides and herbicides, to encourage organic farming.

But the move and its implementation have been criticised.

“We are not against organic farming, but against sub-standard chemical fertilisers which were being imported,” said Namal Karunaratne, national organiser of All Ceylon Farms Federation.

However, he added that “the answer to that is not banning imports overnight.”

Some farmers say the rapid switch could significantly cut production.

“The productivity of the organic fertiliser is less than chemical fertilisers, it would decrease our production and make our survival more difficult,” said HC Hemakumara, President of Ampara district joint farmers association.

About 90% of Sri Lanka’s farmers use chemicals, according to a survey in July.

And the highest dependence on chemical fertilisers was among those growing rice, rubber and tea.

Tea accounts for 10% of export income, and some producers have said they may lose up to 50% of their crop production.

Prof Sabine Zikeli, of the Centre for Organic Farming at the University of Hohenheim in Germany, says a rapid transition to organic could threaten a country’s food security.

“You can’t simply change these conventional cropping systems, you need transition periods,” she says.

“In organic farming, the normal transition period to adapt….about three years or even longer, depending on the country.”

In 2008, Bhutan introduced a policy of going 100% organic by 2020.

But it fell a long way short of achieving this target and a recent study shows yields from the organic farming it has introduced have been substantially lower, leading to a rise in dependence on imports.

Sri Lanka could now face a similar situation, Prof Zikeli, who co-authored this study, says.

And its current economic crisis could add to the threats to its food security.

State Minister Ajith Nivard Cabraal has blamed the opposition for “false reports” about food shortages.

However, long queues have been observed for items such as sugar, rice, lentils and milk powder.

Ramya Sriyani, who was in the queue at a state-run supermarket in Gampaha near Colombo, said that she had had to wait about an hour, and then was not able to buy rice or milk powder as they had run out.

Sri Lanka is running low on foreign exchange – and the money it has is going towards debt settlement.

Its foreign reserves stood at $2.8bn (£2bn) at the end of July, down from $7.5bn in November 2019, when the government took office.

And it has outstanding foreign debts of about $4bn, on which it has to pay interest.

And that could affect essential imported items – such as sugar, wheat, dairy products and medical supplies – which might all face growing supply problems.