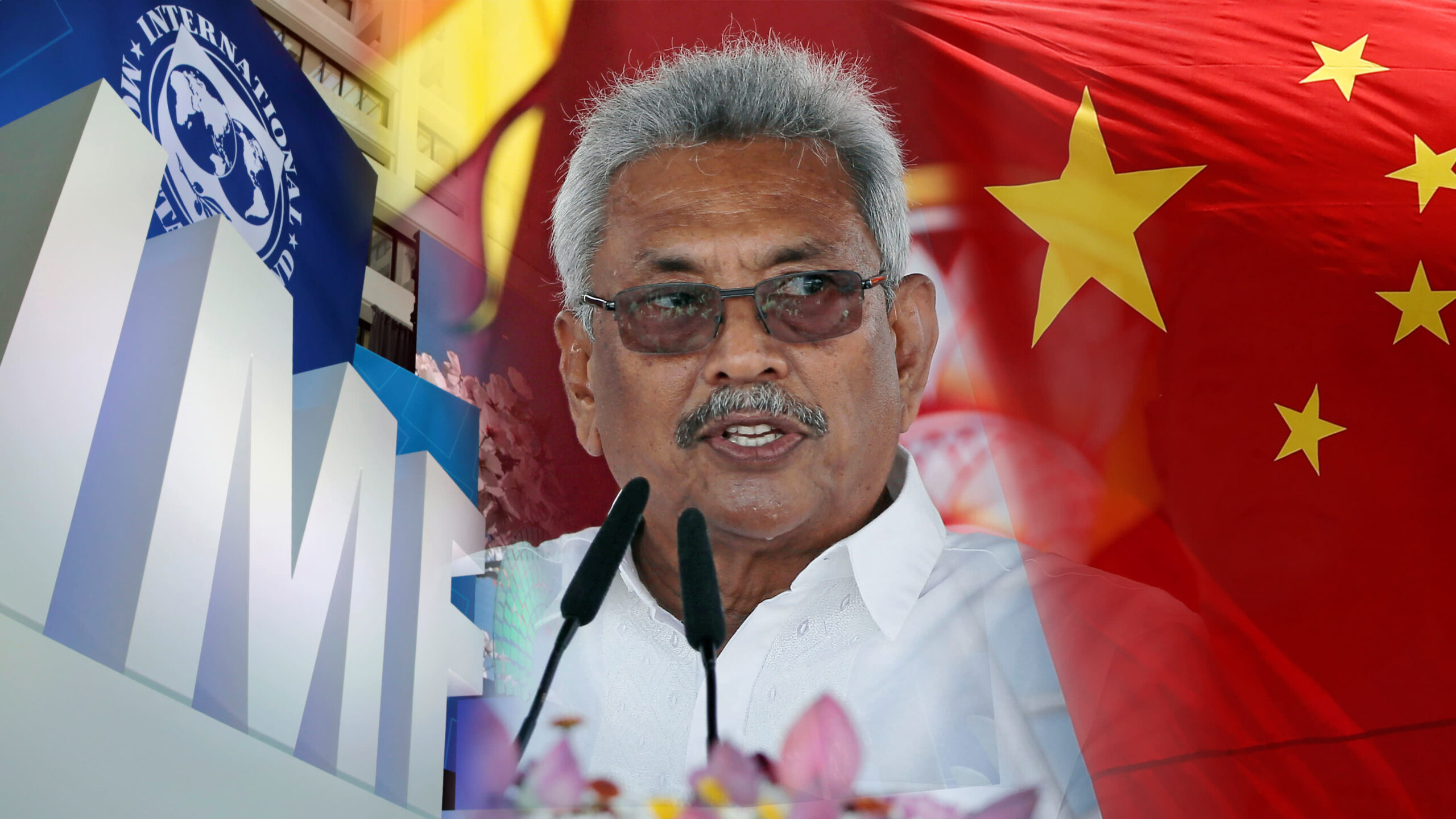

Sri Lanka has just been knocked by a tuk-tuk, hit by a bus, and is being dragged along the road. The country is dangerously low on foreign reserves, struggling to pay creditors, facing import restrictions leading to shortages, and seen overnight price hikes on essentials. Though exacerbated by COVID, the underlying conditions for the crisis have been in the making for years. The Government of Sri Lanka (GOSL) may dislike the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) programs, but if Sri Lanka is to ever pull itself out of its current quagmire it needs the IMF.

Central Bank Governor Nivard Cabraal and MP Vasudeva Nanayakkara vehemently oppose the program because of the conditions the IMF imposes on the country. “Even if we die, we will not seek assistance from the IMF,” Vasudeva told Parliament in November. Instead of dismissing IMF assistance, Vasudeva and other officials should view it as physical therapy that will enable Sri Lanka to start walking on its own two feet again.

Sri Lanka’s situation is dire. The country, unfortunately, checks all boxes on the IMF’s list of why crises may occur. Inappropriate fiscal and monetary policies? Check. An exchange rate fixed at an inappropriate level? Check. A weak financial system? Check. Political instability and/or weak institutions? Check. A natural disaster or an external shock? Check, we have that too, with COVID still prevalent. Bingo!

The IMF states that crises usually result in sharp slowdowns in growth, higher unemployment, lower incomes, and greater uncertainty in countries that can lead to deep recessions. These outcomes are inevitable unless Sri Lanka has someone to help exercise it back to health.

So why does the Government shun the IMF? Resorting instead to taking two Panadols, sleeping and hoping to magically walk again painlessly in the morning, without ever addressing the underlying issues. One reason is the short-term no conditions attached loans Sri Lanka receives to plaster over its wounds: loans from India; China; an IMF distribution of pandemic assistance; and, a currency swap with Bangladesh—considered one of the UN’s Least Developed Countries but now coming to Sri Lanka’s rescue.

As the lender of last resort, the IMF will provide Sri Lanka with financial support to restore economic stability, while ensuring it does not fall into a debt spiral. The IMF will design a loan program, aimed at fixing structural issues, in collaboration with the Government. And just as a physio rehabilitates with painful exercises, the IMF program conditions will get Sri Lanka walking again, even if the exercises will be painful in the short-term.

Tax revenues will need to be increased to improve the fiscal position and operational capacity of GOSL. A painful exercise going against public sentiment, but easier to stomach when conditionality also improves accountability. The 2016 IMF program included having the ministry update its tax administration system; publish tax expenditure statements as part of the budget; and increasing tax collection by simplifying the tax code, auditing dodgers, and broadening the tax base. Sri Lanka ranks among Somalia, Yemen, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia in the top 10 least tax-collecting countries. Currently, Sri Lanka’s tax revenue is 9.5% of GDP, down from ~20% in the 1990s, while studies estimate that 13% is needed for a state to effectively carryout its duties.

The next painful exercises will be improved public financial management and governance and accountability of state-owned enterprises. The Ceylon Electricity Board and SriLankan Airlines are among the State’s loss-making entities that are not commercially viable. This leads to GOSL constantly bailing them out while increasing its exposure to the foreign loan market.

Just as Vasudeva fears, the IMF will also ask for a devaluation of the rupee as part of its rehab program, which could lead to an increase in prices over time. The MP, however, discounts the upsides of devaluation: It improves export competitiveness, narrows the trade deficit, and can reduce the cost of some interest payments. As Sri Lanka’s international reserves rapidly declined from $ 8 billion to $ 2 billion since 2020—the lowest level recorded ever—GOSL will need to stop propping up the rupee.

Yes, Cabraal and GOSL, IMF conditionality is difficult, and it certainly is a painful rehabilitation process. While encouraging fiscal discipline and structural adjustments is the primary tenet of the program, an IMF program is more than just money to shore up short-term crises. The IMF can provide a comprehensive assessment on Sri Lanka’s fiscal, monetary, and governance reforms. It can monitor its performance indicators. And a successful completion of the program will reduce Sri Lanka’s borrowing rates and attract creditors once again.

A condition-based program with the IMF, the hated physio, is crucial if Sri Lanka is to stand up on its own two feet again; delays in accepting this truth will only lead to exacerbating the crisis and prolonging the suffering.

(The writer is finishing up his Master’s program at the Harvard Kennedy School and previously worked at the IMF for four

years working on program

negotiations with developing countries.)